History of the Lincoln Highway

Join us on a journey as we travel along the Lincoln Highway in Illinois, delving into its historical timeline and uncovering the significant events and developments that have shaped this iconic route over the years. Scroll down ↓

Dream of the “Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway”

1912 In 1912, the United States had over 2.5 million miles of disconnected roads, mostly dirt, which were often bumpy and dusty in dry weather and impassable in wet weather. There were limited improved and safe roads, with many of the good roads concentrated within towns and cities.

In September 1912, Carl G. Fisher first announced his idea for a "Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway" that would span the country. He began actively promoting his dream on September 10 at a dinner meeting with many of his friends from the automobile industry at the Deutsches Haus in his hometown of Indianapolis.

The following slides will take you through the history and development of the Lincoln Highway and its lasting impact on our national roadways.

Photograph: Carl G. Fisher, undated. Courtesy of The Library of Congress – George Grantham Bain Collection.

Establishment of the Lincoln Highway Association

1913 To complete Fisher's dream of a “Coast to Coast Rock Highway," the Lincoln Highway Association (LHA) was formally incorporated at the organization's national headquarters in the Dime Savings Bank Building in Detroit, Michigan, on July 1, 1913.

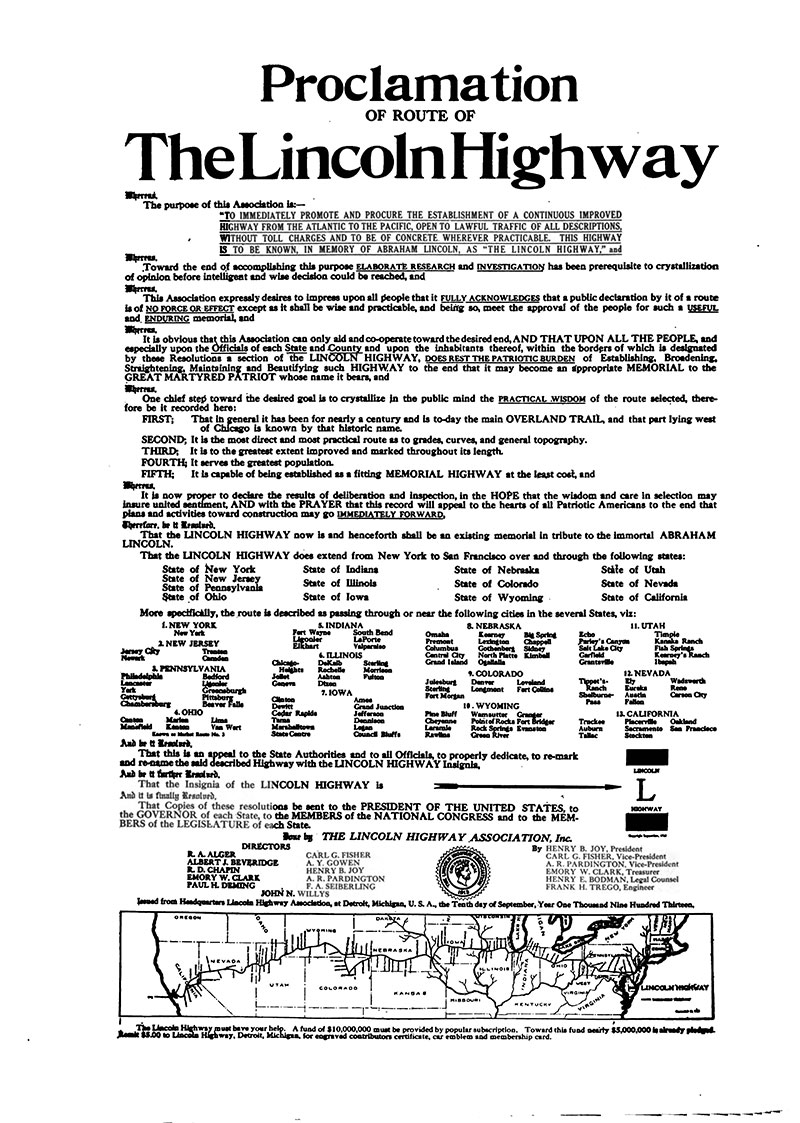

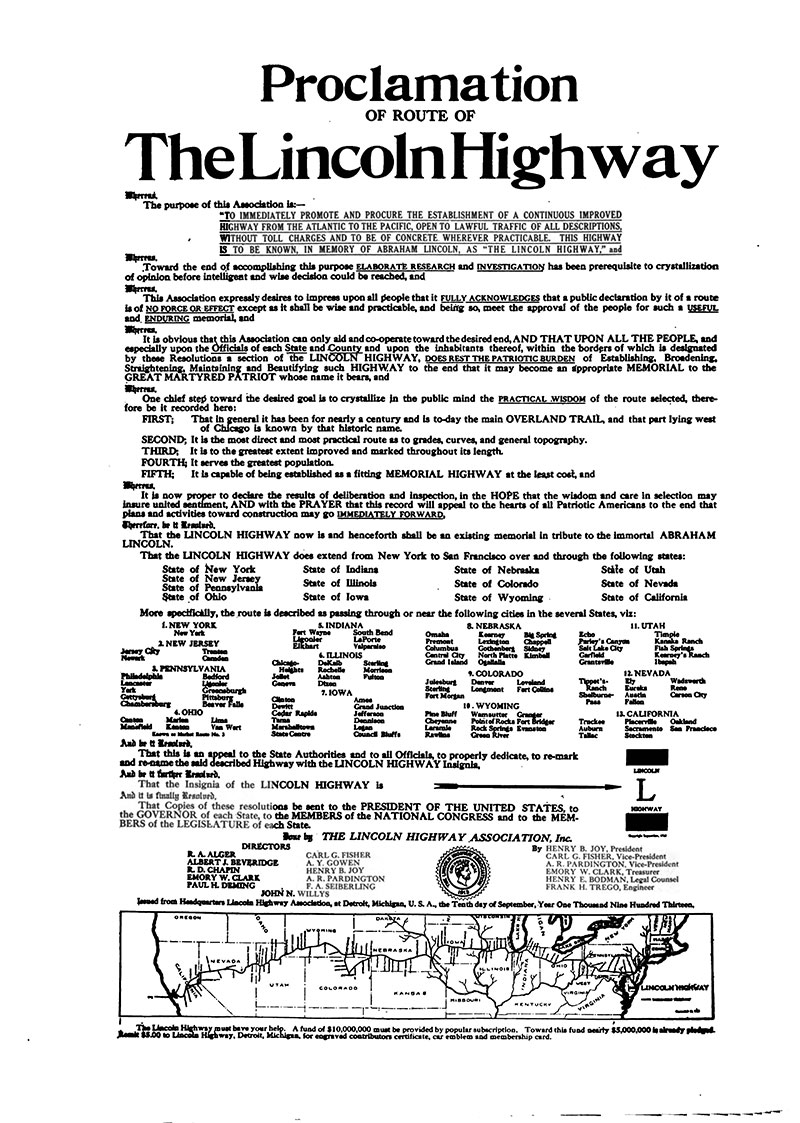

Photograph: Proclamation of Route of The Lincoln Highway, issued by the Lincoln Highway Association, September 10, 1913. Courtesy of the American Motorist.

- “To procure the establishment of a continuous improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, open to lawful travel of all description without toll charges: such highway to be known, in the memory of Abraham Lincoln, as the 'Lincoln Highway.' ”

- The mission of the Lincoln Highway Association, as stated in the organization's Articles of Incorporation, July 1, 1913.

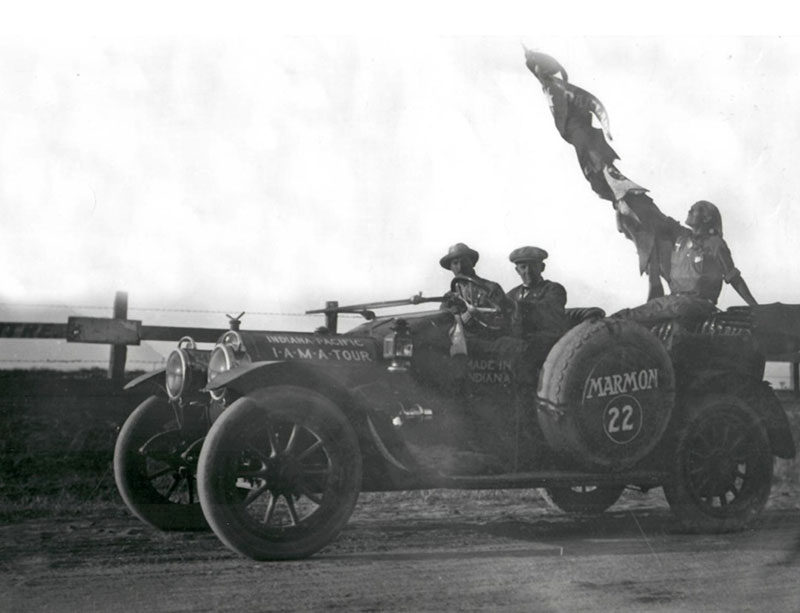

Hoosier Tour: Indiana to the Pacific

1913 Within an hour of incorporation, several members of the newly formed LHA set out with the Indiana–Pacific Automobile Manufacturers Association (I.A.M.A.) and the Hoosier Motor Club to stimulate public interest in a transcontinental road. The convoy left Indianapolis on July 1, 1913, and arrived in San Francisco 34 days later on August 3.

Before the automobilists even set out, word of the trip catalyzed $500,000 in road improvements, including the construction of more than 30 new concrete bridges along the route. Some of these bridges, which had already been planned, were expedited for the tour.

Adoption of the Official Route of the Lincoln Highway

1913 The fledgling organization's first efforts focused on identifying the route and fundraising. The LHA developed a preliminary route that bypassed large cities in favor of rural areas, which showcased the nation's natural beauty. The route utilized existing trails and roads, including Native American Trails and early stagecoach routes, as much as possible to minimize the need and cost for grading and planning. The LHA adopted the highway's official route on September 4, 1913.

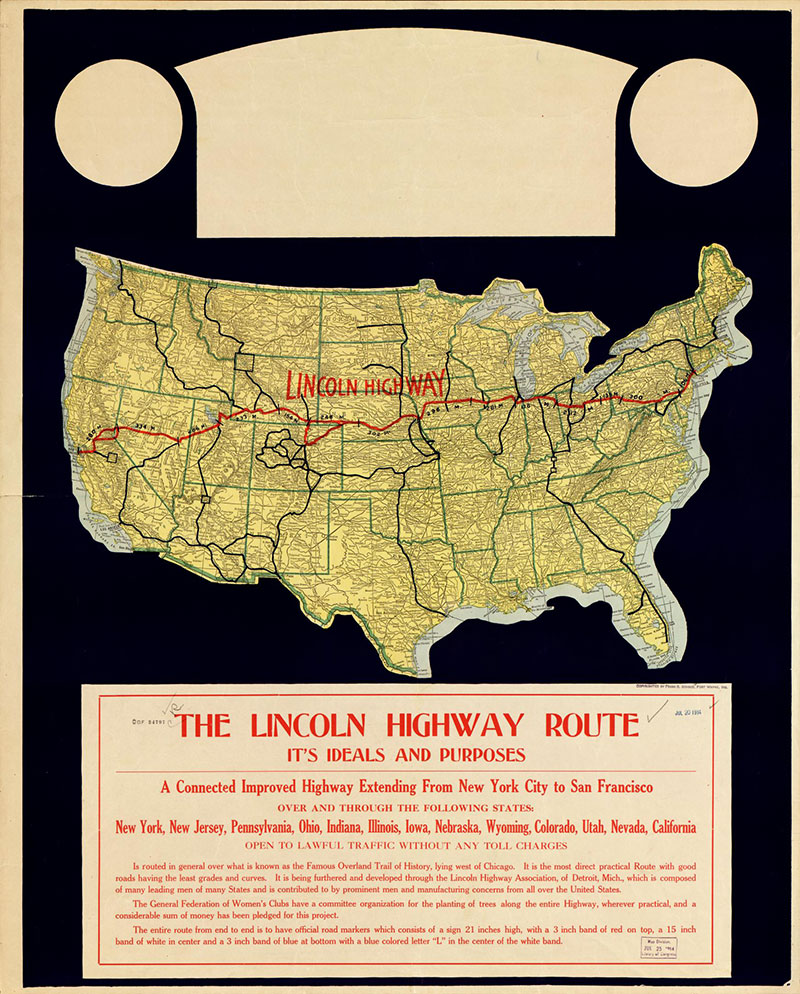

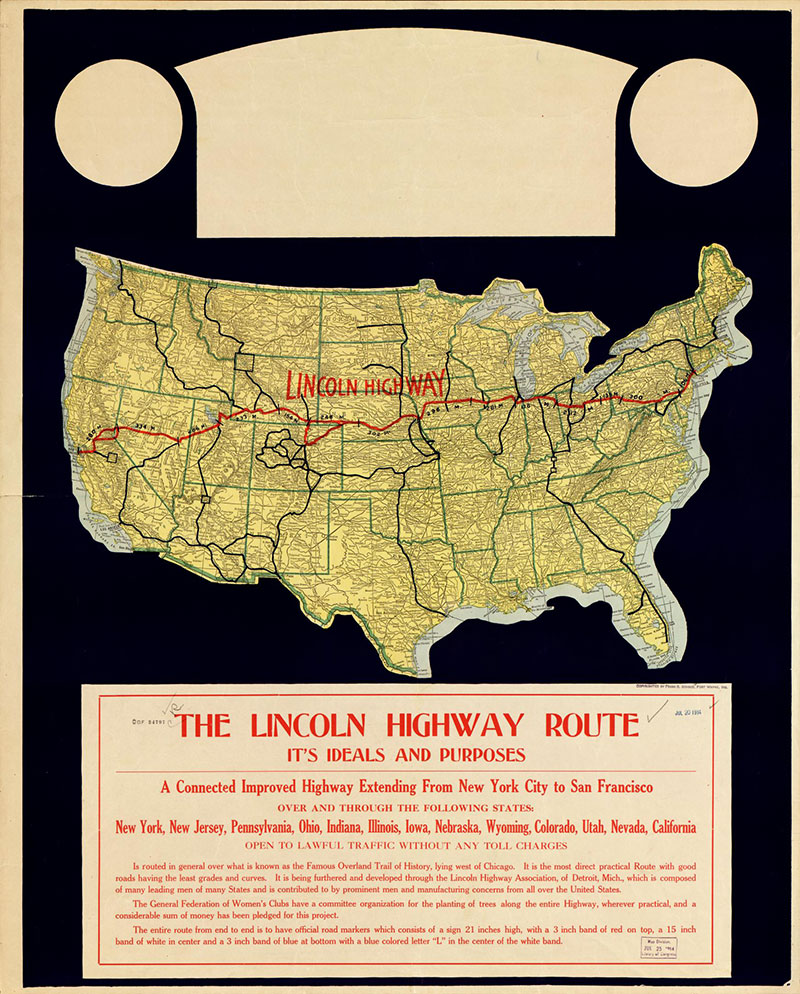

Photograph: The Lincoln Highway route: its ideals and purposes: a connected improved highway extending from New York City to San Francisco ..., 1914. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

- “The route of the Lincoln Highway must, when finally adopted, be governed by the following factors: the directness of the route between New York and San Francisco; second, points of scenic and historic interest and centers of population, between these points which can be most advantageously and economically incorporated; third, the character and the amount of support afforded this association by the local communities which will receive the direct and immediate benefit of the establishment of this great memorial to Abraham Lincoln.“

- Arthur R. Paddington, Secretary of the Lincoln Highway Association, 1913.

Fundraising for the Lincoln Highway

1913 The new route was estimated to cost approximately $10 million for labor and materials. To generate funds, the LHA solicited pledges from automobile manufacturers and accessory companies equivalent to 1% of their annual sales. In return, the association would devise ways to promote each company’s products along the Lincoln Highway. The response from auto companies was favorable, with one million dollars generated within just two weeks.

The LHA then turned to the public to supplement funds from the auto industry, as federal government and state leaders refused to provide financial support for the project.

Additional funds were generated with memorabilia and membership sales. The memberships were sold at five dollars and included a small “LH” bumper-mounted plaque. With these funds, the LHA began planning, clearing brush, grading, graveling, and earth tamping, as well as marking the Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco.

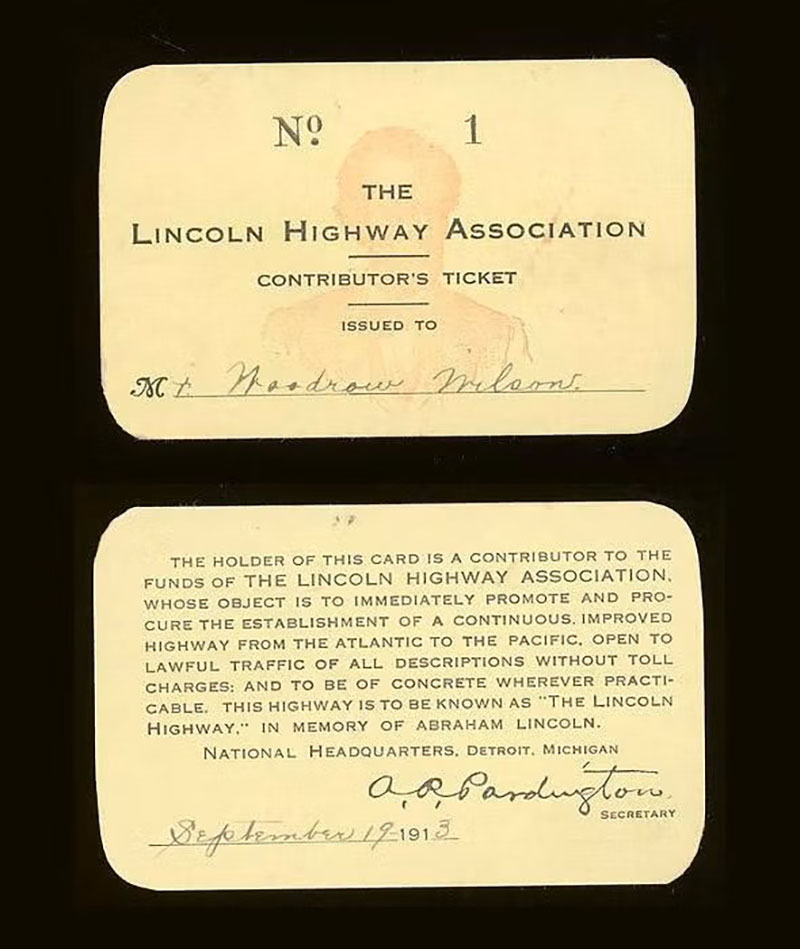

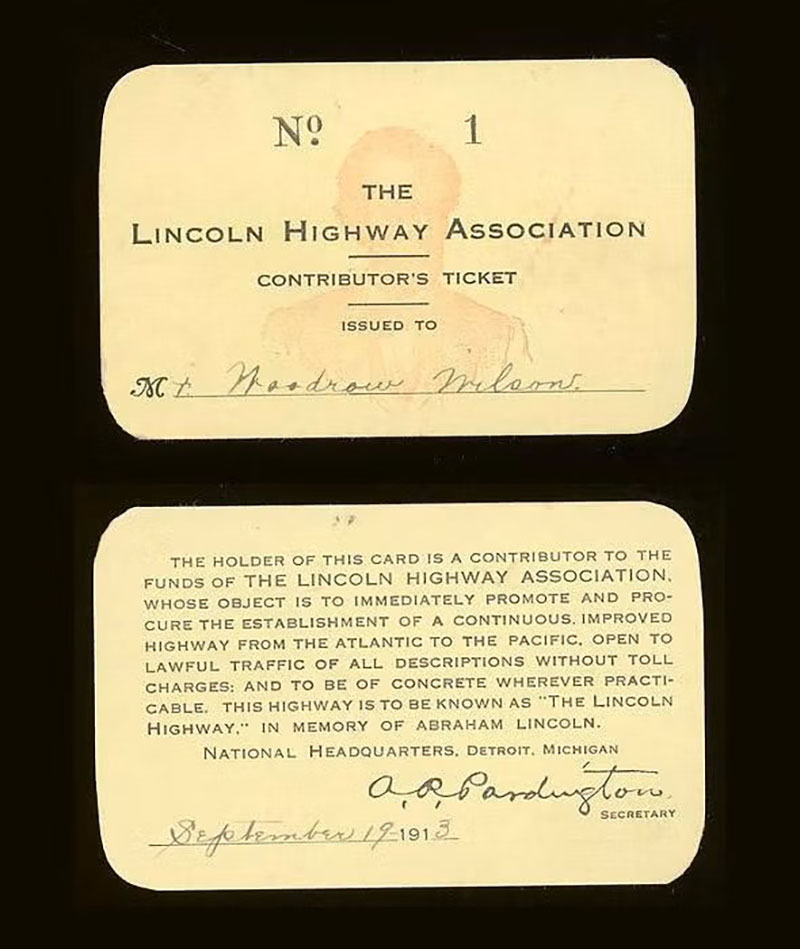

Photograph: View of the first Lincoln Highway Association membership card, issued to President Woodrow Wilson. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Dedication of the Lincoln Highway

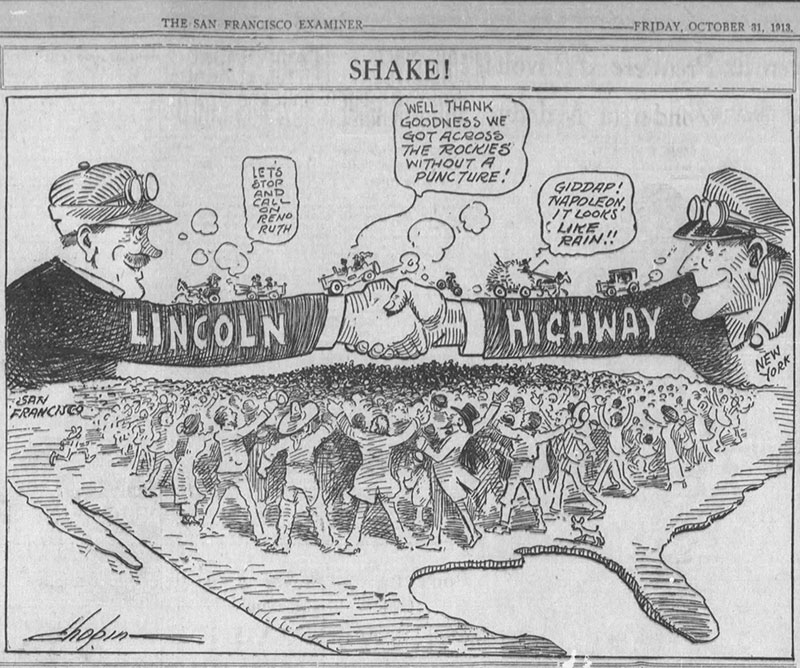

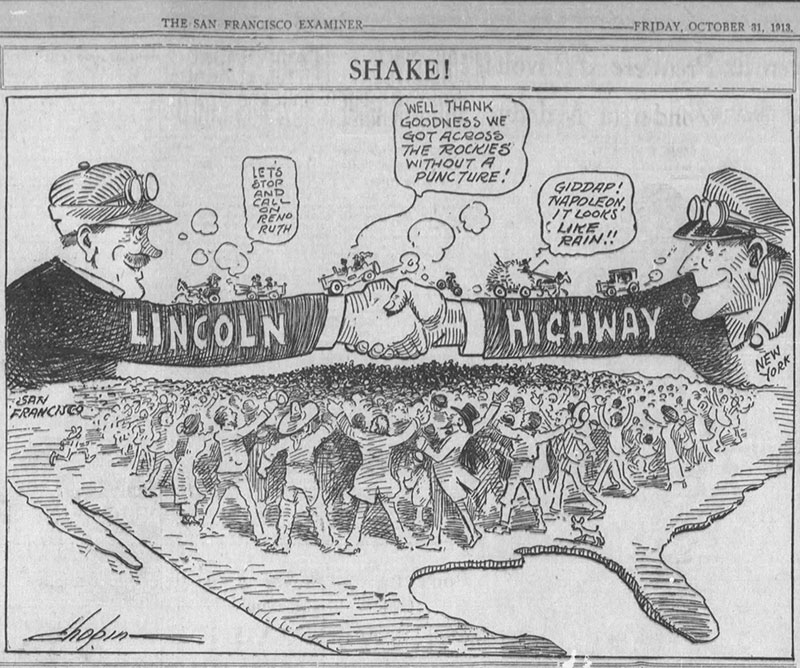

1913 On October 31, 1913, the LHA officially dedicated the route of the Lincoln Highway. The milestone was celebrated across the 13 states through which the highway traveled. Bonfires and fireworks, concerts, and parades illuminated hundreds of cities. In at least two locations, the streets were swept and washed so dances could be held on the highway.

Photograph: Dedication announcement for the Lincoln Highway, the San Francisco Examiner, October 31, 1913.

A First in Illinois: Malta’s “Seedling Mile”

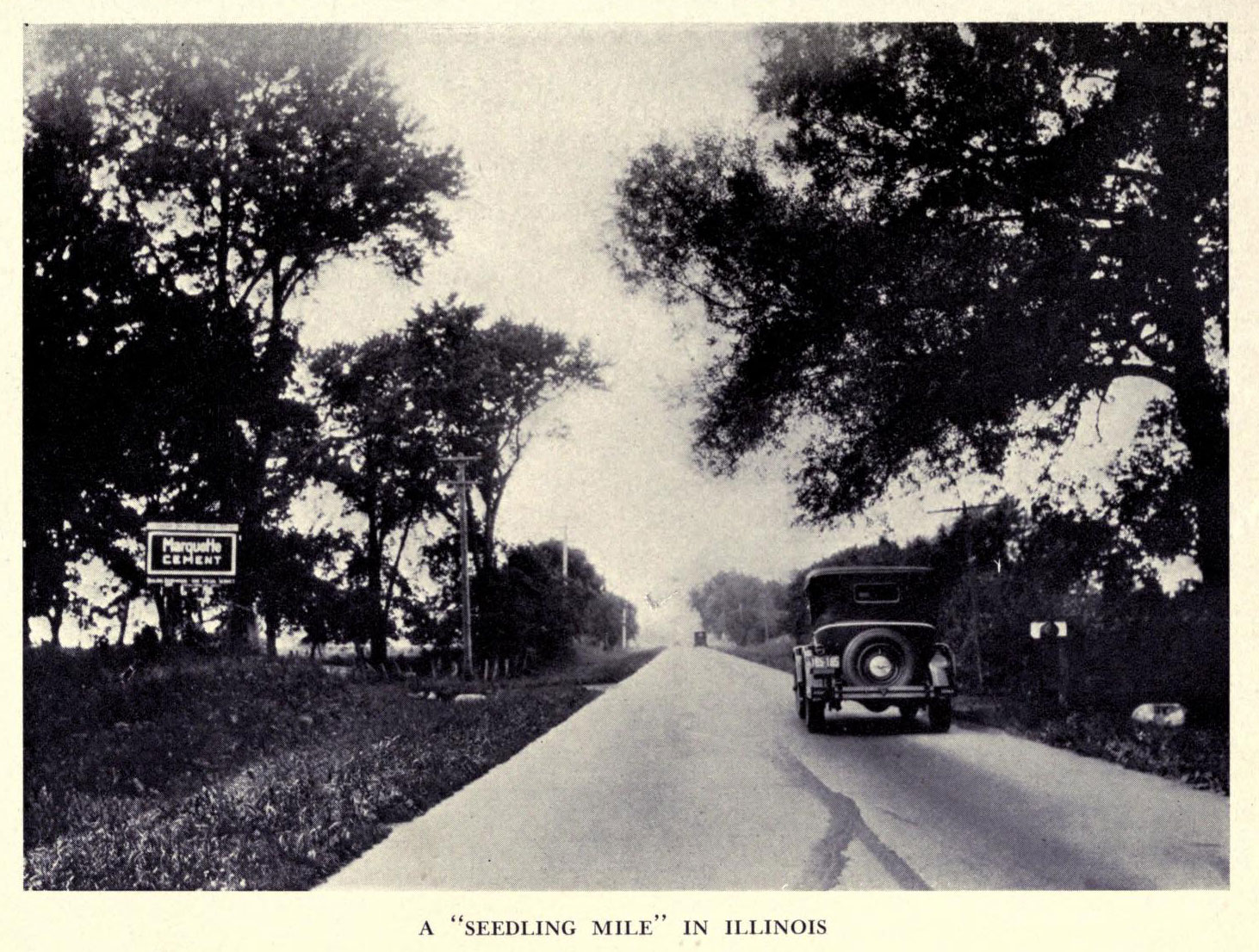

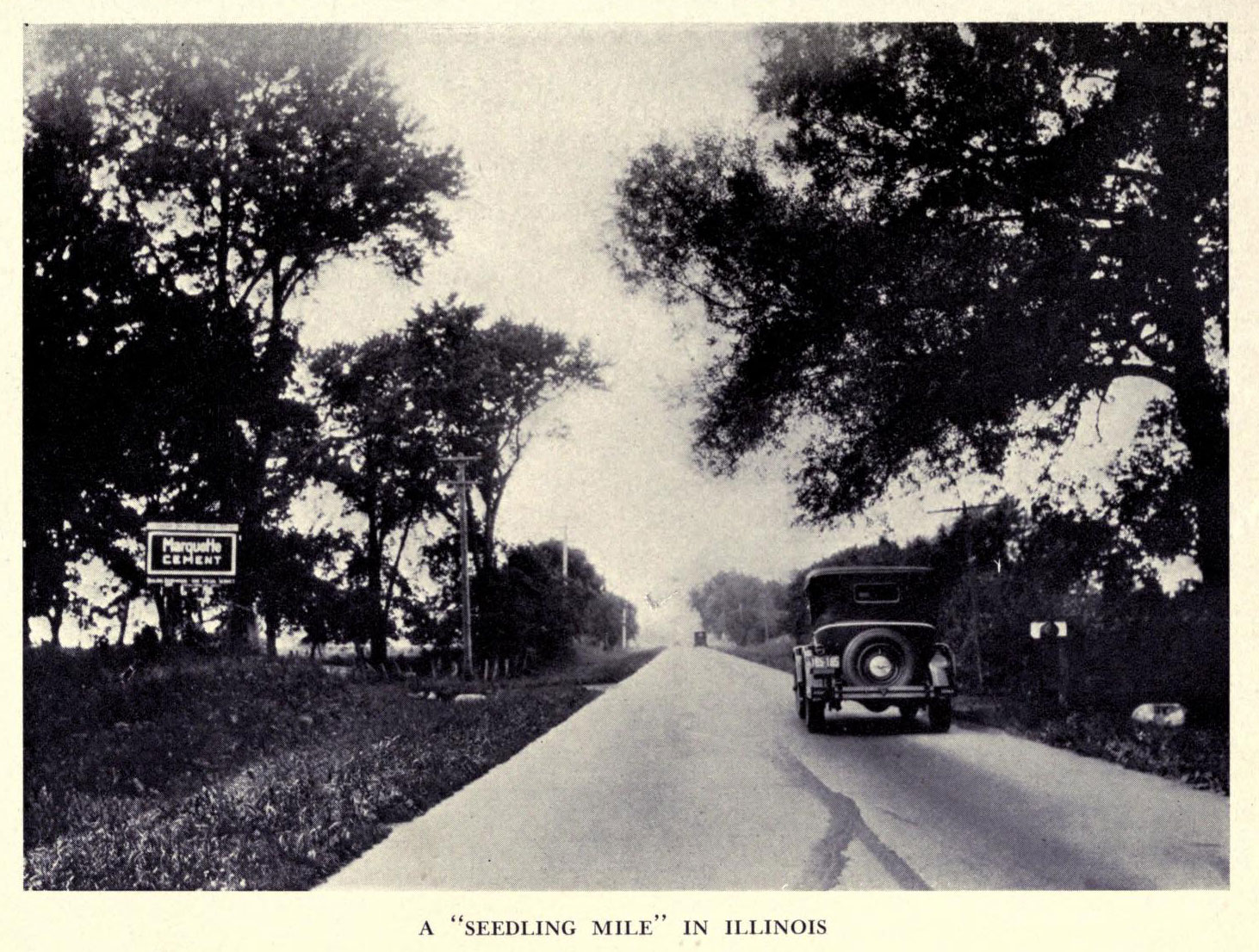

1914 Public support for the “rock highway” was spurred by the development of the “Seedling Mile.” Each “Mile” was typically one mile long and paved with concrete along the Lincoln Highway route. Seedling miles were typically constructed in rural communities, which were plagued by muddy, unmaintained dirt roads and would benefit from the installation, which, in turn, would promote road improvements.

The first Seedling Mile was completed in October 1914 in the farming community of Malta, DeKalb County, Illinois. The mile was constructed through a combined effort between the citizens of Malta, the LHA, and the Marquette Cement Company, also marking one of the first uses of concrete for road surfacing in the United States. With the successful installation of Seedling Miles, the Lincoln Highway was further propelled through the donation of millions of barrels of cement by several companies, including Lehigh Portland Cement and Marquette Cement. Illinois received a donation of 8,000 barrels of cement, of which 2,000 barrels were contributed to Malta.

Photograph: View of the Seedling Mile in Malta, undated. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

Mooseheart Seedling Mile

1915 Following the Malta Seedling Mile, that same year, a .75-mile of roadway was laid in Mooseheart, Kane County, Illinois. This mile was fully funded by the Loyal Order of the Moose and constructed by over 1,000 volunteers from the Mooseheart community.

Photograph: View of the concrete section constructed, between Mooseheart and Batavia, Kane County, Illinois, undated. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

- “There was not, in 1900, or even 1905, a single mile of rural paved road, as pavement now is known, in the United States. It was into this condition that the automobile was born, and within a very few years, the owners of motor cars had wearied of driving over the streets of their home towns, or the driveways of their parks, and were clamoring for durable road construction.”

- The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History, 1935.

Morrison Seedling Mile

1915 Efforts to complete the Lincoln Highway through Illinois continued through the 1910s. In 1915, Whiteside County, Illinois, generated enough funds for a three-mile Seedling Mile in the small town of Morrison.

Photograph: View of the completed Lincoln Highway between Morrison and Fulton, Illinois, 1926. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

- “[The Whiteside County] example had so stirred neighboring counties that they, too, were anxious for allotments of cement. Farmers were offering to haul road materials free, and both urban and rural residents were contributing funds for improving the Lincoln Highway.”

- The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History, 1935.

The Lincoln Highway Reaches the Pacific

1915 Nearing its goal to complete the highway by 1915, the LHA intensified its promotion of the Lincoln Highway to tourists en route to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

In 1915, the LHA produced "The Three-Mile Picture Show." Directed by Henry Ostermann, the film promoted the Lincoln Highway, featuring tourists traveling across the country on their way to the Exposition. It was shown almost continually at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition from September until the fair closed on December 4, 1915.

On the LHA's return trip back east, the group showed the film in cities and towns that had sponsored its financing.

- ‘See America’ is almost a duty of all patriotic citizens. At least, see all one can is a duty. The motor car offers the most exhilarating, the most interesting, the most enjoyable, the most instructive means of ‘seeing.’ Having thus covered over 250,000 miles, I speak from experience.”

- Charles Henry Davis, President of the National Highways Association, 1915.

Photograph: The official Lincoln Highway Car dipping its wheels in the Pacific Ocean, the San Francisco Examiner, August 1915.

Federal Aid Road Act of 1916

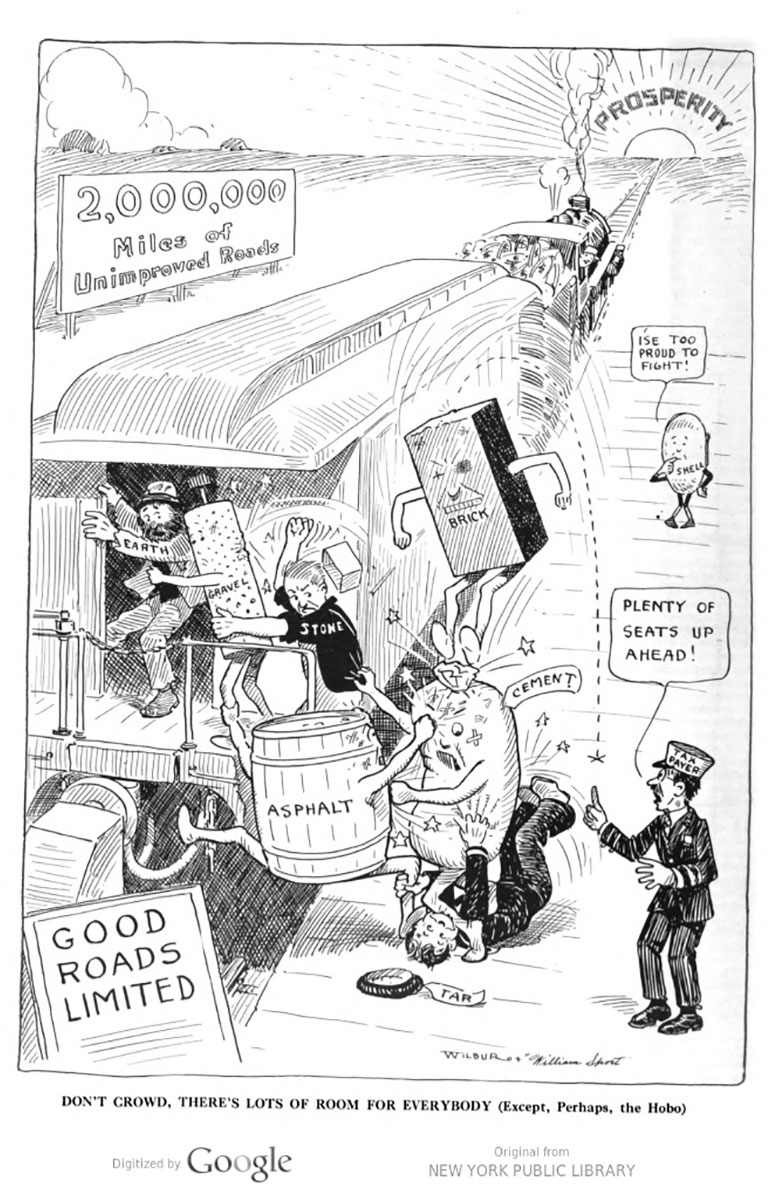

1916 Following the completion of the Lincoln Highway in 1915, there was a positive shift in support for federally funded and constructed roads.

A significant milestone for better roads was the passing of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 on July 11 of that year. It established the Federal-Aid Highway Program, which generated federal funds for road construction and planning and also assigned a highway agency for each state.

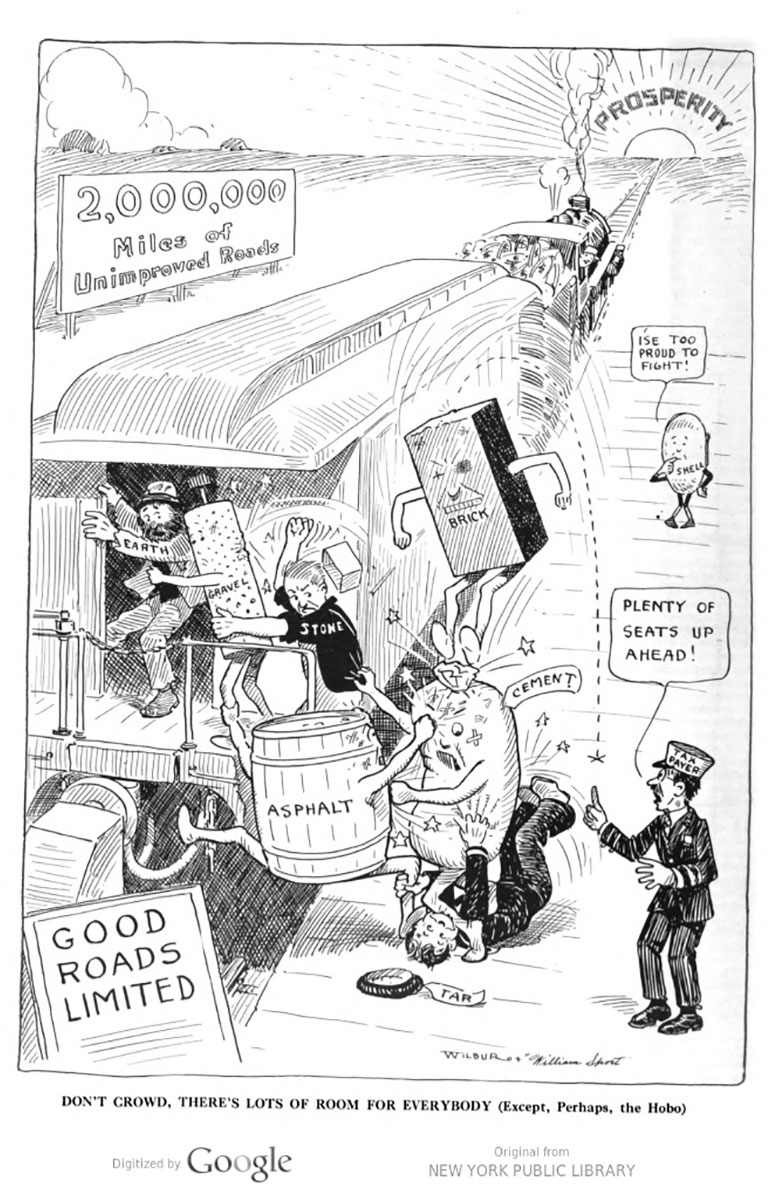

Although an improvement in support of national roads, the primary purpose of the Federal Aid Road Act was to support state government efforts to construct rural post roads and roads used for the “transportation of Interstate commerce, military supplies or postal matters” (Federal-aid bill, H.R. 7617).

Photograph: Illustration depicting the "fights for better road materials" from the magazine Better Roads and Streets, 1916.

The “Zero Milestone”

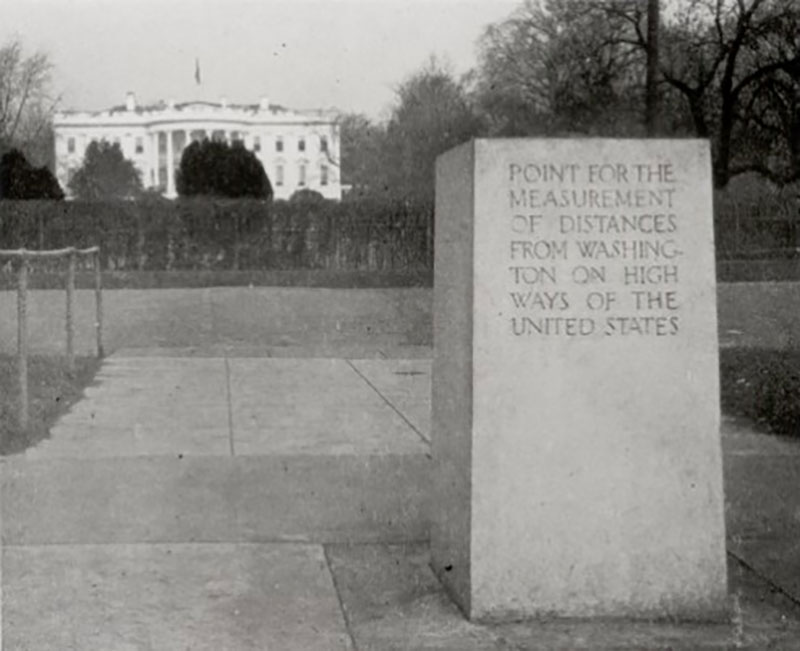

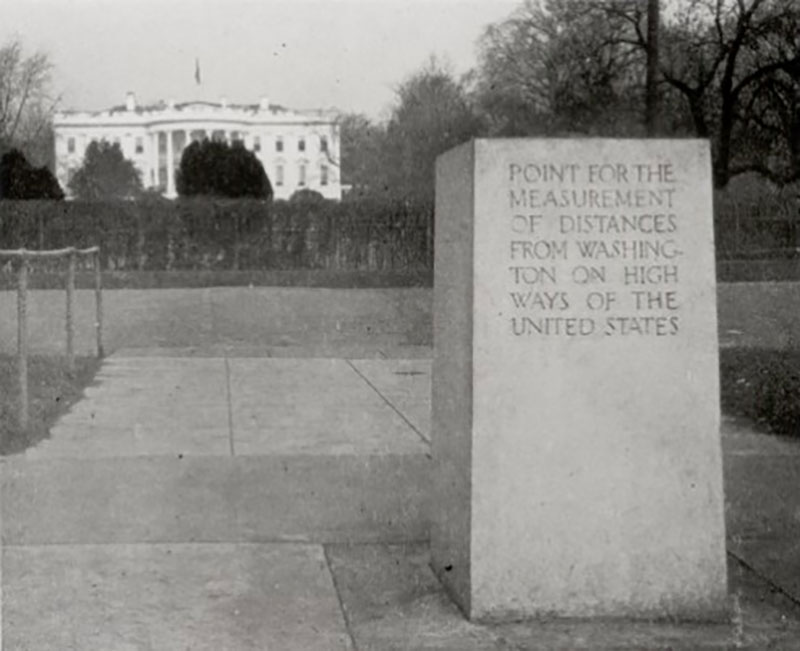

1919 However, the initiation of World War I in April 1917 diverted funds and materials away from the highway program. The program was revived, in part, by 1919 with the creation of the “Zero Milestone” in Washington, D.C., just south of the White House. This point serves as the symbolic official starting point for measuring highway distances from Washington, D.C.

Inspired by ancient Rome's Golden Milestone, the current Zero Milestone monument was conceived by Dr. S. M. Johnson, a prominent advocate of the Good Roads Movement.

On July 7, 1919, a temporary marker for the Zero Milestone was dedicated on the Ellipse south of the White House during ceremonies launching the Transcontinental Motor Convoy.

On June 5, 1920, Congress authorized the Secretary of War to erect the current monument. The monument was designed by Washington architect Horace Peaslee and approved by the Commission of Fine Arts. It was presented as a gift from the Lee Highway Association and formally dedicated on June 4, 1923.

Photograph: Zero Milestone, 1923. Courtesy of the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration.

Transcontinental Motor Convoy

1919 The Zero Milestone served as the starting point of the first Transcontinental Motor Convoy. Following the June 28, 1919, signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the army vehicle convoy carried 81 motorized army vehicles, a crew of approximately 258 enlisted soldiers, and 24 officers across the country between July 7 and September 1, 1919, in celebration of victory. In total, the convoy traveled 3,251 miles over 62 days.

For the first time, large, heavy military vehicles could travel easily from the east to the west coast, utilizing the transcontinental Lincoln Highway. Notably, one of the convoy members was future President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a lieutenant colonel in the Army at the time. The journey would later influence his prioritization of the country's national highway system during his presidency (1953-1961).

Photograph: Transcontinental Motor Convoy, 1919, included in The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History.

The Ideal Section

1923 The LHA continued its pioneering efforts in 1923 by establishing a one-and-a-half-mile “Ideal Section” of the highway in Lake County, Indiana. Designed by landscape architect Jens Jensen, the well-designed section sets a standard for future highway construction, cost, grading, plantings, and equipment. It was also one of the first “24-Hour Roads” with lighting provided by General Electric. Funding for the project was generated by the LHA and a large donation from the United States Rubber Company.

Photograph: Billboard sign describing Ideal Section, Indiana, undated. Photograph taken by the Chicago Architectural Photographing Company. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

Dissolution of the Lincoln Highway Association

1926-1928 In 1926, three years after the construction of the Ideal Section, the LHA realized the substantial completion of the 3,389-mile Lincoln Highway. That same year, the U.S. Numbered Highway System was established, incorporating a significant part of the Lincoln Highway. Having formally achieved the organization's core mission, the LHA disbanded on December 31, 1927.

The following year, the route was officially marked and dedicated in honor of Abraham Lincoln on September 1, 1928. As part of the ceremony, groups of Boy Scouts throughout each state installed 3,000 concrete markers along the route.

The legacy of the LHA would be carried into the following decades with the onset of the Great Depression, which signaled a new era for the improvement of the nation's road infrastructure.

Photograph: Newspaper article from the Progress-Bulletin, August 4, 1928.

- The Lincoln Highway is little more than a memory, but it has left its achievement - a network of paved and dustless highways, known by the numbers.

- Lawton Wright for the Saturday Evening Post, February 1939.

The Great Depression

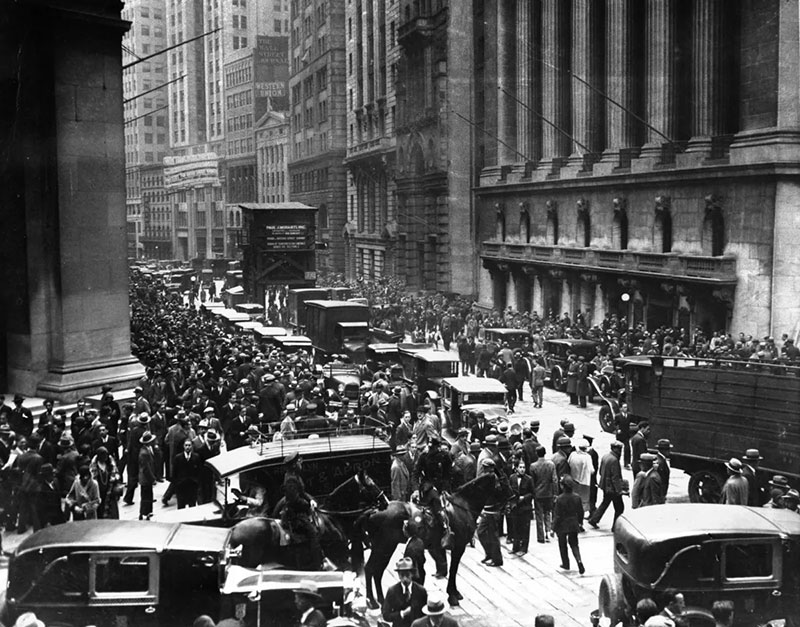

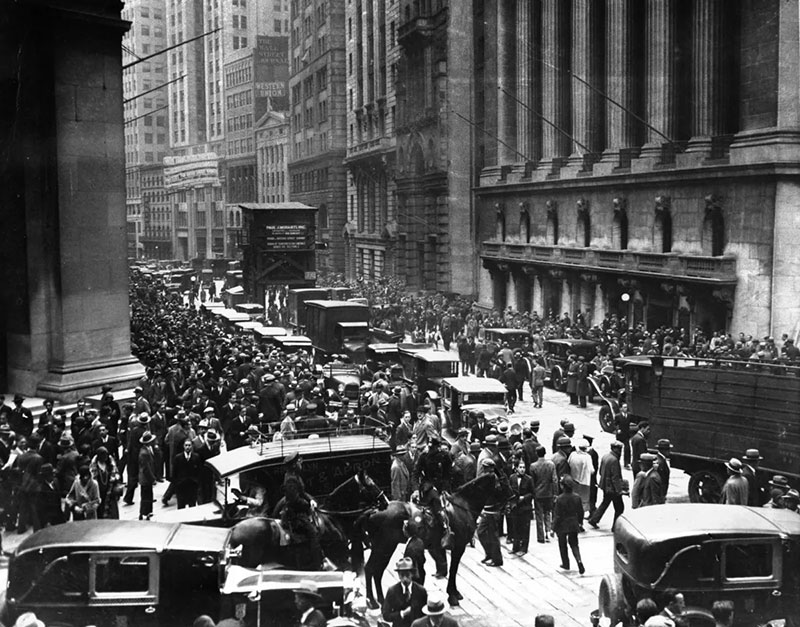

1929-1939 The booming growth of highway improvement programs in the U.S. slowed significantly after the U.S. Stock Market crashed on October 24, 1929. By 1933, one-quarter of the country’s labor force was unemployed, and the country’s banking systems had collapsed, creating the Great Depression. Simultaneously, the agricultural Great Plains region was struck by ten years of severe drought known as the Dust Bowl. An estimated 2.5 million people were compelled to migrate west, abandoning farms across the region.

Photograph: In this photograph, panic ensued as hundreds of investors milled about the New York Stock Exchange (the building is at right) after the stock market crashed on October 29, 1929. Courtesy of The Chicago Tribune.

The New Deal and the Groundwork for the Interstate Highway System

1933-1944 In 1933, newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt promised to bring the country out of the Great Depression. To do this, Roosevelt established a series of government programs, collectively known as The New Deal, to provide relief, recovery, and reform. The individual programs created under the New Deal focused on addressing unemployment, stabilizing the banking system, and providing social security.

As part of the New Deal, Roosevelt established the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which provided jobs and economic relief through the employment of millions of Americans on public works projects.

Part of the public works projects focused on significant improvements to the country's transportation infrastructure. Together, the programs constructed millions of miles of roads, bridges, and tunnels, and also improved urban streets and airports. The WPA is credited with building over 650,000 miles of roads and 75,000 bridges, while the PWA funded over 11,000 road projects.

This work ultimately led to the restructuring of transportation infrastructure improvement programs through the 1944 amendment of the Federal-Aid Highway Act, first passed in 1916 as the Federal Aid Road Act. Under the act, a 50–50 formula for subsidizing the construction of national highways and secondary (or "feeder") roads was established between the federal and state governments.

Additionally, under the 1944 amendment, the United States Congress authorized the construction of up to 40,000 miles of roadways. However, it would be over a decade before work began on the future "National System of Interstate Highways."

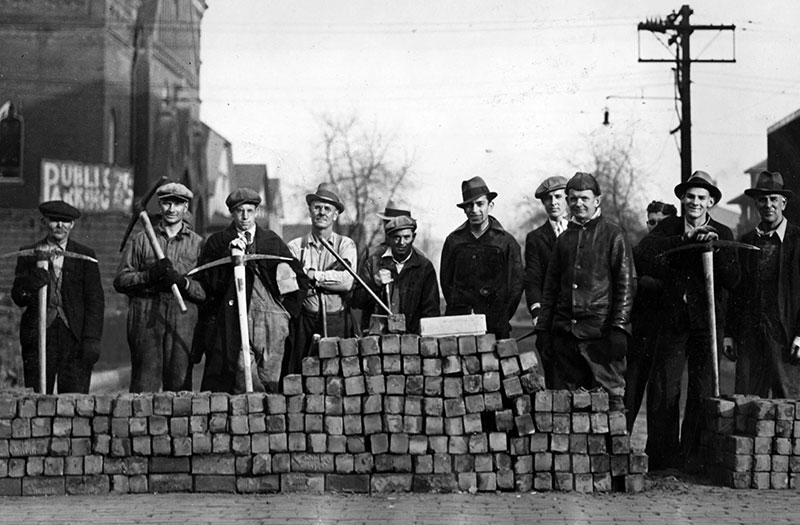

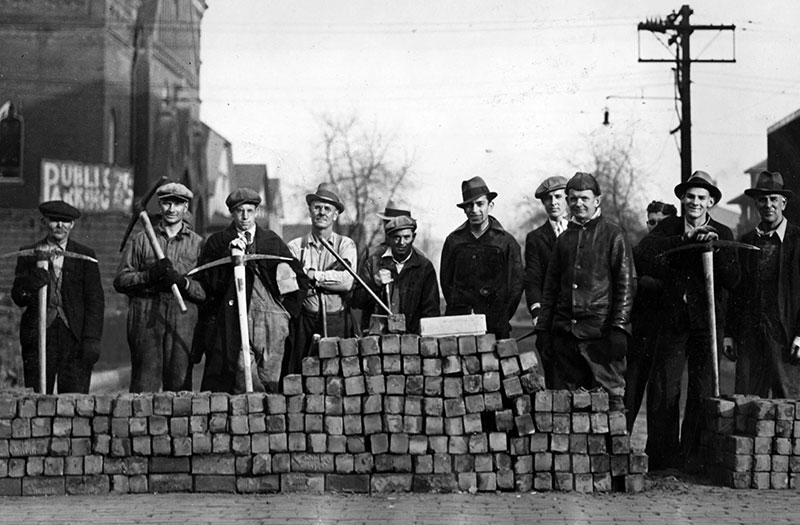

Photograph: This photograph captures a group of men employed to make improvements to Clinton and Homan streets as part of the public work projects in November 1933. Courtesy of The Chicago Tribune.

Establishment of the National System of Interstate Highways

1947 As a result of World War II (1939-1945), the United States diverted funds toward the war effort, leading to deteriorating infrastructure and hazardous road conditions.

In 1947, President Harry S. Truman, a member of the American Road Builders’ Association, the Kansas City Automobile Club, and former president of the National Old Trails Road Association, hosted the Presidential Highway Safety Conference, urging state representatives, national highway organizations, and the general public to prioritize highway safety.

Truman's advocacy led to the establishment of the Action Program, which resulted in the creation of a Uniform Vehicle Code and Model Traffic Ordinance, the introduction of traffic education in schools, the strengthening of traffic laws, the improvement of highway design, and the development of licensing programs.

Additionally, the Federal-Aid Highway Act was amended for a second time in 1948, laying the groundwork for the Interstate Highway System, which was established as part of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.

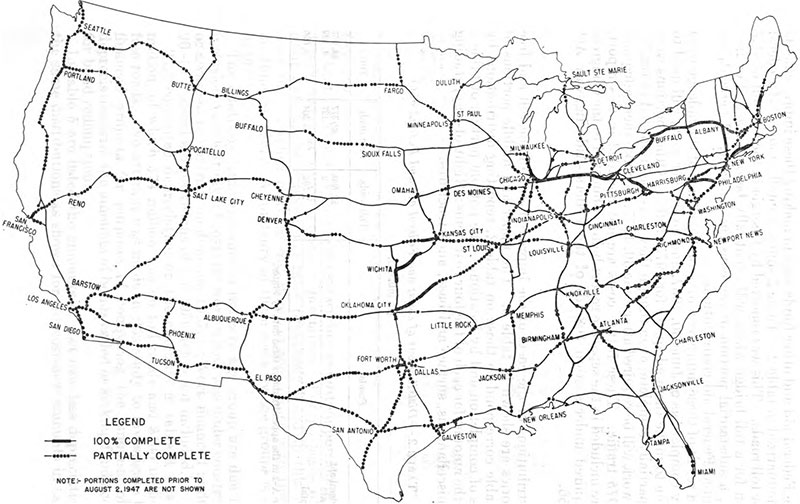

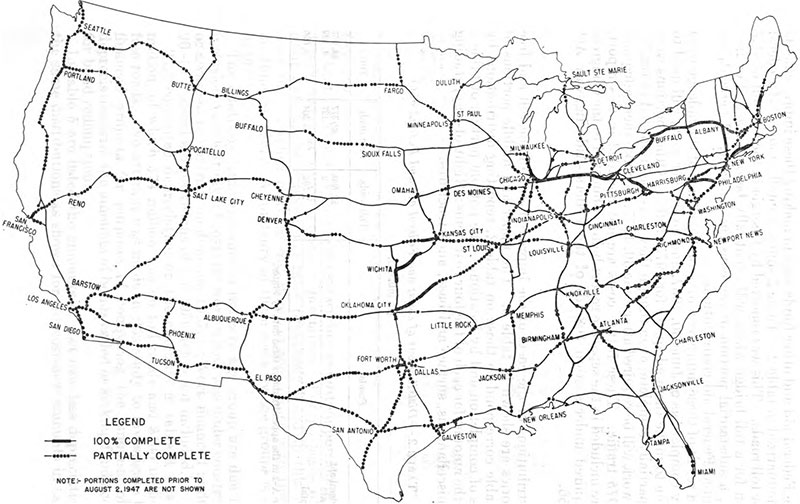

Photograph: Map depicting the proposed National System of Interstate Highways drafted by the Public Roads Administration, 1947. Courtesy of The Eno Center for Transportation.

Construction of the Interstate Highway System

1955-1967 In 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected President. Before his election, Eisenhower expressed concerns about the lack of a unified, high-capacity, and safe nationwide system of highways. Eisenhower's concerns were fueled by his experience as part of the 1919 Transcontinental Motor Convoy and later as a General in the United States Army during World War II.

As President, Eisenhower championed the establishment of the nation's Interstate Highway System through his crucial support of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The act provided funding for 40,000 miles of limited-access interstate highways nationwide, making it one of the largest public works projects ever completed in the country. By 1959, the first highways in Illinois had opened, including portions of Interstates 90, 94, and 294, followed by Interstate 57 in the 1960s.

However, with the construction of the Interstate Highway System, travelers now bypassed the Lincoln Highway and the small, rural communities along the way for faster, more direct routes.

Photograph: Construction of I-57 on August 17, 1966, two miles south of Chebanse in Iroquois County, Illinois. Courtesy of the Secretary of State Archivist.

Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act

1991 In 1991, the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act laid the groundwork for the creation of the National Scenic Byway and All-American Road programs. Both programs were established to recognize outstanding examples of scenic, historic, recreational, cultural, archaeological, and natural beauty along the nation's roadways. The Act also provided funding to support the preservation of historic roads and the communities located along them. Together, these programs established new avenues for heritage tourism and economic development along America’s historic routes, including the Lincoln Highway.

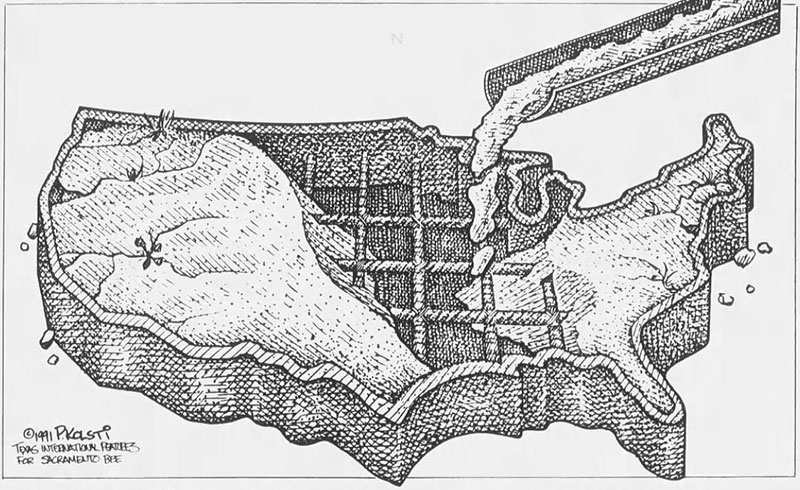

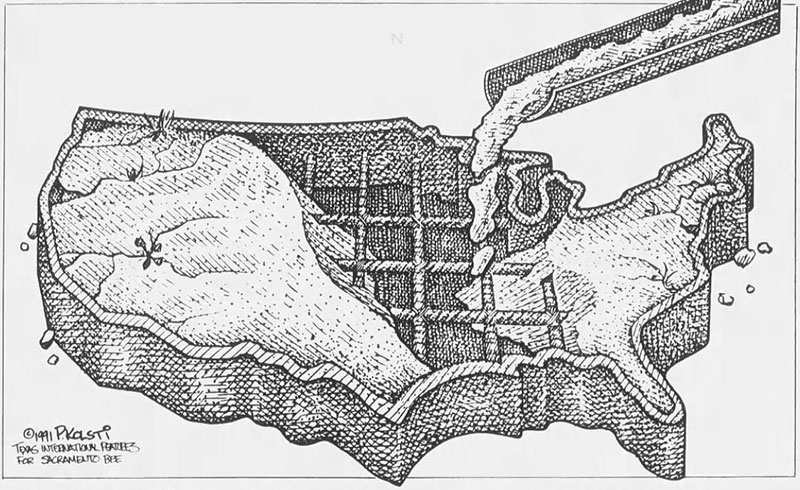

Photograph: This graphic was designed by Paul Kolsti for the Sacramento Bee to support the Federal Highway Act, encouraging infrastructure improvements, on April 28, 1991.

Reactivation of the LHA

1992 On October 31, 1992, the national Lincoln Highway Association was reactivated. The organization was established by Gregory M. Franzwa, who had formerly participated in the preservation of wagon trails in California and Oregon. Other participants included the author of The Lincoln Highway: Main Street Across America, Drake Hokanson, and Joyce and Bob Ausberger, who identified lost segments in Iowa and advocated for preservation by listing several resources on the National Register of Historic Places.

Photograph: The reactivated Lincoln Highway Association in Ogden, Iowa, October 31, 1992. Courtesy of Lincoln Highway News.

Designation as a National Scenic Byway

2000 In Illinois, the state chapter of the Lincoln Highway Association submitted the route for designation as a National Scenic Byway by the Federal Highway Administration. The Illinois segment of the Lincoln Highway, composed of 178.8 miles, is the first and only section to receive this designation in its entirety.

Photograph: "An Illinois Seedling Mile," undated. Courtesy of the Lincoln Highway Digital Image Collection at the University of Michigan Library.

Dream of the “Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway”

1912 In 1912, the United States had over 2.5 million miles of disconnected roads, mostly dirt, which were often bumpy and dusty in dry weather and impassable in wet weather. There were limited improved and safe roads, with many of the good roads concentrated within towns and cities.

In September 1912, Carl G. Fisher first announced his idea for a "Coast-to-Coast Rock Highway" that would span the country. He began actively promoting his dream on September 10 at a dinner meeting with many of his friends from the automobile industry at the Deutsches Haus in his hometown of Indianapolis.

The following slides will take you through the history and development of the Lincoln Highway and its lasting impact on our national roadways.

Photograph: Carl G. Fisher, undated. Courtesy of The Library of Congress – George Grantham Bain Collection.

Establishment of the Lincoln Highway Association

1913 To complete Fisher's dream of a “Coast to Coast Rock Highway," the Lincoln Highway Association (LHA) was formally incorporated at the organization's national headquarters in the Dime Savings Bank Building in Detroit, Michigan, on July 1, 1913.

Photograph: Proclamation of Route of The Lincoln Highway, issued by the Lincoln Highway Association, September 10, 1913. Courtesy of the American Motorist.

- “To procure the establishment of a continuous improved highway from the Atlantic to the Pacific, open to lawful travel of all description without toll charges: such highway to be known, in the memory of Abraham Lincoln, as the 'Lincoln Highway.' ”

- The mission of the Lincoln Highway Association, as stated in the organization's Articles of Incorporation, July 1, 1913.

Hoosier Tour: Indiana to the Pacific

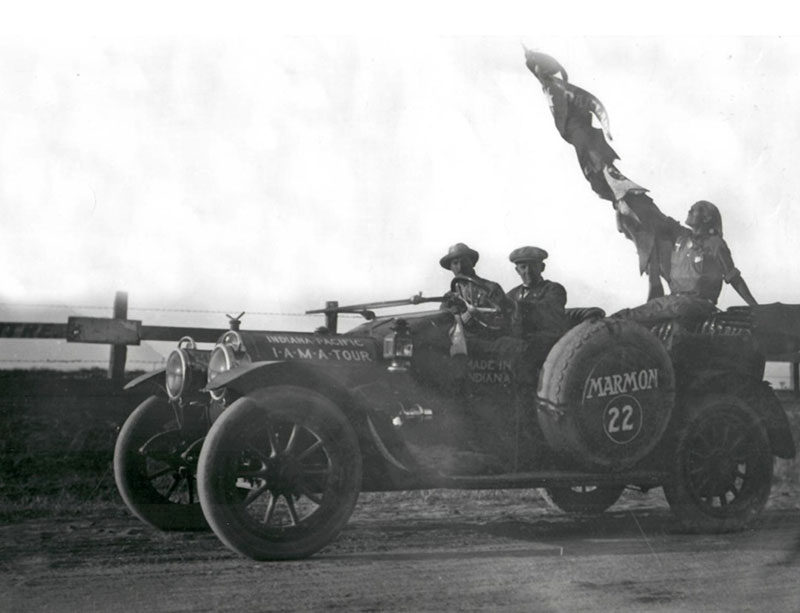

1913 Within an hour of incorporation, several members of the newly formed LHA set out with the Indiana–Pacific Automobile Manufacturers Association (I.A.M.A.) and the Hoosier Motor Club to stimulate public interest in a transcontinental road. The convoy left Indianapolis on July 1, 1913, and arrived in San Francisco 34 days later on August 3.

Before the automobilists even set out, word of the trip catalyzed $500,000 in road improvements, including the construction of more than 30 new concrete bridges along the route. Some of these bridges, which had already been planned, were expedited for the tour.

Adoption of the Official Route of the Lincoln Highway

1913 The fledgling organization's first efforts focused on identifying the route and fundraising. The LHA developed a preliminary route that bypassed large cities in favor of rural areas, which showcased the nation's natural beauty. The route utilized existing trails and roads, including Native American Trails and early stagecoach routes, as much as possible to minimize the need and cost for grading and planning. The LHA adopted the highway's official route on September 4, 1913.

Photograph: The Lincoln Highway route: its ideals and purposes: a connected improved highway extending from New York City to San Francisco ..., 1914. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

- “The route of the Lincoln Highway must, when finally adopted, be governed by the following factors: the directness of the route between New York and San Francisco; second, points of scenic and historic interest and centers of population, between these points which can be most advantageously and economically incorporated; third, the character and the amount of support afforded this association by the local communities which will receive the direct and immediate benefit of the establishment of this great memorial to Abraham Lincoln.“

- Arthur R. Paddington, Secretary of the Lincoln Highway Association, 1913.

Fundraising for the Lincoln Highway

1913 The new route was estimated to cost approximately $10 million for labor and materials. To generate funds, the LHA solicited pledges from automobile manufacturers and accessory companies equivalent to 1% of their annual sales. In return, the association would devise ways to promote each company’s products along the Lincoln Highway. The response from auto companies was favorable, with one million dollars generated within just two weeks.

The LHA then turned to the public to supplement funds from the auto industry, as federal government and state leaders refused to provide financial support for the project.

Additional funds were generated with memorabilia and membership sales. The memberships were sold at five dollars and included a small “LH” bumper-mounted plaque. With these funds, the LHA began planning, clearing brush, grading, graveling, and earth tamping, as well as marking the Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco.

Photograph: View of the first Lincoln Highway Association membership card, issued to President Woodrow Wilson. Courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

Dedication of the Lincoln Highway

1913 On October 31, 1913, the LHA officially dedicated the route of the Lincoln Highway. The milestone was celebrated across the 13 states through which the highway traveled. Bonfires and fireworks, concerts, and parades illuminated hundreds of cities. In at least two locations, the streets were swept and washed so dances could be held on the highway.

Photograph: Dedication announcement for the Lincoln Highway, the San Francisco Examiner, October 31, 1913.

A First in Illinois: Malta’s “Seedling Mile”

1914 Public support for the “rock highway” was spurred by the development of the “Seedling Mile.” Each “Mile” was typically one mile long and paved with concrete along the Lincoln Highway route. Seedling miles were typically constructed in rural communities, which were plagued by muddy, unmaintained dirt roads and would benefit from the installation, which, in turn, would promote road improvements.

The first Seedling Mile was completed in October 1914 in the farming community of Malta, DeKalb County, Illinois. The mile was constructed through a combined effort between the citizens of Malta, the LHA, and the Marquette Cement Company, also marking one of the first uses of concrete for road surfacing in the United States. With the successful installation of Seedling Miles, the Lincoln Highway was further propelled through the donation of millions of barrels of cement by several companies, including Lehigh Portland Cement and Marquette Cement. Illinois received a donation of 8,000 barrels of cement, of which 2,000 barrels were contributed to Malta.

Photograph: View of the Seedling Mile in Malta, undated. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

Mooseheart Seedling Mile

1915 Following the Malta Seedling Mile, that same year, a .75-mile of roadway was laid in Mooseheart, Kane County, Illinois. This mile was fully funded by the Loyal Order of the Moose and constructed by over 1,000 volunteers from the Mooseheart community.

Photograph: View of the concrete section constructed, between Mooseheart and Batavia, Kane County, Illinois, undated. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

- “There was not, in 1900, or even 1905, a single mile of rural paved road, as pavement now is known, in the United States. It was into this condition that the automobile was born, and within a very few years, the owners of motor cars had wearied of driving over the streets of their home towns, or the driveways of their parks, and were clamoring for durable road construction.”

- The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History, 1935.

Morrison Seedling Mile

1915 Efforts to complete the Lincoln Highway through Illinois continued through the 1910s. In 1915, Whiteside County, Illinois, generated enough funds for a three-mile Seedling Mile in the small town of Morrison.

Photograph: View of the completed Lincoln Highway between Morrison and Fulton, Illinois, 1926. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

- “[The Whiteside County] example had so stirred neighboring counties that they, too, were anxious for allotments of cement. Farmers were offering to haul road materials free, and both urban and rural residents were contributing funds for improving the Lincoln Highway.”

- The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History, 1935.

The Lincoln Highway Reaches the Pacific

1915 Nearing its goal to complete the highway by 1915, the LHA intensified its promotion of the Lincoln Highway to tourists en route to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco.

In 1915, the LHA produced "The Three-Mile Picture Show." Directed by Henry Ostermann, the film promoted the Lincoln Highway, featuring tourists traveling across the country on their way to the Exposition. It was shown almost continually at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition from September until the fair closed on December 4, 1915.

On the LHA's return trip back east, the group showed the film in cities and towns that had sponsored its financing.

- ‘See America’ is almost a duty of all patriotic citizens. At least, see all one can is a duty. The motor car offers the most exhilarating, the most interesting, the most enjoyable, the most instructive means of ‘seeing.’ Having thus covered over 250,000 miles, I speak from experience.”

- Charles Henry Davis, President of the National Highways Association, 1915.

Photograph: The official Lincoln Highway Car dipping its wheels in the Pacific Ocean, the San Francisco Examiner, August 1915.

Federal Aid Road Act of 1916

1916 Following the completion of the Lincoln Highway in 1915, there was a positive shift in support for federally funded and constructed roads.

A significant milestone for better roads was the passing of the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916 on July 11 of that year. It established the Federal-Aid Highway Program, which generated federal funds for road construction and planning and also assigned a highway agency for each state.

Although an improvement in support of national roads, the primary purpose of the Federal Aid Road Act was to support state government efforts to construct rural post roads and roads used for the “transportation of Interstate commerce, military supplies or postal matters” (Federal-aid bill, H.R. 7617).

Photograph: Illustration depicting the "fights for better road materials" from the magazine Better Roads and Streets, 1916.

The “Zero Milestone”

1919 However, the initiation of World War I in April 1917 diverted funds and materials away from the highway program. The program was revived, in part, by 1919 with the creation of the “Zero Milestone” in Washington, D.C., just south of the White House. This point serves as the symbolic official starting point for measuring highway distances from Washington, D.C.

Inspired by ancient Rome's Golden Milestone, the current Zero Milestone monument was conceived by Dr. S. M. Johnson, a prominent advocate of the Good Roads Movement.

On July 7, 1919, a temporary marker for the Zero Milestone was dedicated on the Ellipse south of the White House during ceremonies launching the Transcontinental Motor Convoy.

On June 5, 1920, Congress authorized the Secretary of War to erect the current monument. The monument was designed by Washington architect Horace Peaslee and approved by the Commission of Fine Arts. It was presented as a gift from the Lee Highway Association and formally dedicated on June 4, 1923.

Photograph: Zero Milestone, 1923. Courtesy of the U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration.

Transcontinental Motor Convoy

1919 The Zero Milestone served as the starting point of the first Transcontinental Motor Convoy. Following the June 28, 1919, signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the army vehicle convoy carried 81 motorized army vehicles, a crew of approximately 258 enlisted soldiers, and 24 officers across the country between July 7 and September 1, 1919, in celebration of victory. In total, the convoy traveled 3,251 miles over 62 days.

For the first time, large, heavy military vehicles could travel easily from the east to the west coast, utilizing the transcontinental Lincoln Highway. Notably, one of the convoy members was future President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a lieutenant colonel in the Army at the time. The journey would later influence his prioritization of the country's national highway system during his presidency (1953-1961).

Photograph: Transcontinental Motor Convoy, 1919, included in The Lincoln Highway: The Story of a Crusade That Made Transportation History.

The Ideal Section

1923 The LHA continued its pioneering efforts in 1923 by establishing a one-and-a-half-mile “Ideal Section” of the highway in Lake County, Indiana. Designed by landscape architect Jens Jensen, the well-designed section sets a standard for future highway construction, cost, grading, plantings, and equipment. It was also one of the first “24-Hour Roads” with lighting provided by General Electric. Funding for the project was generated by the LHA and a large donation from the United States Rubber Company.

Photograph: Billboard sign describing Ideal Section, Indiana, undated. Photograph taken by the Chicago Architectural Photographing Company. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

Dissolution of the Lincoln Highway Association

1926-1928 In 1926, three years after the construction of the Ideal Section, the LHA realized the substantial completion of the 3,389-mile Lincoln Highway. That same year, the U.S. Numbered Highway System was established, incorporating a significant part of the Lincoln Highway. Having formally achieved the organization's core mission, the LHA disbanded on December 31, 1927.

The following year, the route was officially marked and dedicated in honor of Abraham Lincoln on September 1, 1928. As part of the ceremony, groups of Boy Scouts throughout each state installed 3,000 concrete markers along the route.

The legacy of the LHA would be carried into the following decades with the onset of the Great Depression, which signaled a new era for the improvement of the nation's road infrastructure.

Photograph: Newspaper article from the Progress-Bulletin, August 4, 1928.

- The Lincoln Highway is little more than a memory, but it has left its achievement - a network of paved and dustless highways, known by the numbers.

- Lawton Wright for the Saturday Evening Post, February 1939.

The Great Depression

1929-1939 The booming growth of highway improvement programs in the U.S. slowed significantly after the U.S. Stock Market crashed on October 24, 1929. By 1933, one-quarter of the country’s labor force was unemployed, and the country’s banking systems had collapsed, creating the Great Depression. Simultaneously, the agricultural Great Plains region was struck by ten years of severe drought known as the Dust Bowl. An estimated 2.5 million people were compelled to migrate west, abandoning farms across the region.

Photograph: In this photograph, panic ensued as hundreds of investors milled about the New York Stock Exchange (the building is at right) after the stock market crashed on October 29, 1929. Courtesy of The Chicago Tribune.

The New Deal and the Groundwork for the Interstate Highway System

1933-1944 In 1933, newly elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt promised to bring the country out of the Great Depression. To do this, Roosevelt established a series of government programs, collectively known as The New Deal, to provide relief, recovery, and reform. The individual programs created under the New Deal focused on addressing unemployment, stabilizing the banking system, and providing social security.

As part of the New Deal, Roosevelt established the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which provided jobs and economic relief through the employment of millions of Americans on public works projects.

Part of the public works projects focused on significant improvements to the country's transportation infrastructure. Together, the programs constructed millions of miles of roads, bridges, and tunnels, and also improved urban streets and airports. The WPA is credited with building over 650,000 miles of roads and 75,000 bridges, while the PWA funded over 11,000 road projects.

This work ultimately led to the restructuring of transportation infrastructure improvement programs through the 1944 amendment of the Federal-Aid Highway Act, first passed in 1916 as the Federal Aid Road Act. Under the act, a 50–50 formula for subsidizing the construction of national highways and secondary (or "feeder") roads was established between the federal and state governments.

Additionally, under the 1944 amendment, the United States Congress authorized the construction of up to 40,000 miles of roadways. However, it would be over a decade before work began on the future "National System of Interstate Highways."

Photograph: This photograph captures a group of men employed to make improvements to Clinton and Homan streets as part of the public work projects in November 1933. Courtesy of The Chicago Tribune.

Establishment of the National System of Interstate Highways

1947 As a result of World War II (1939-1945), the United States diverted funds toward the war effort, leading to deteriorating infrastructure and hazardous road conditions.

In 1947, President Harry S. Truman, a member of the American Road Builders’ Association, the Kansas City Automobile Club, and former president of the National Old Trails Road Association, hosted the Presidential Highway Safety Conference, urging state representatives, national highway organizations, and the general public to prioritize highway safety.

Truman's advocacy led to the establishment of the Action Program, which resulted in the creation of a Uniform Vehicle Code and Model Traffic Ordinance, the introduction of traffic education in schools, the strengthening of traffic laws, the improvement of highway design, and the development of licensing programs.

Additionally, the Federal-Aid Highway Act was amended for a second time in 1948, laying the groundwork for the Interstate Highway System, which was established as part of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956.

Photograph: Map depicting the proposed National System of Interstate Highways drafted by the Public Roads Administration, 1947. Courtesy of The Eno Center for Transportation.

Construction of the Interstate Highway System

1955-1967 In 1953, Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected President. Before his election, Eisenhower expressed concerns about the lack of a unified, high-capacity, and safe nationwide system of highways. Eisenhower's concerns were fueled by his experience as part of the 1919 Transcontinental Motor Convoy and later as a General in the United States Army during World War II.

As President, Eisenhower championed the establishment of the nation's Interstate Highway System through his crucial support of the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The act provided funding for 40,000 miles of limited-access interstate highways nationwide, making it one of the largest public works projects ever completed in the country. By 1959, the first highways in Illinois had opened, including portions of Interstates 90, 94, and 294, followed by Interstate 57 in the 1960s.

However, with the construction of the Interstate Highway System, travelers now bypassed the Lincoln Highway and the small, rural communities along the way for faster, more direct routes.

Photograph: Construction of I-57 on August 17, 1966, two miles south of Chebanse in Iroquois County, Illinois. Courtesy of the Secretary of State Archivist.

Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act

1991 In 1991, the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act laid the groundwork for the creation of the National Scenic Byway and All-American Road programs. Both programs were established to recognize outstanding examples of scenic, historic, recreational, cultural, archaeological, and natural beauty along the nation's roadways. The Act also provided funding to support the preservation of historic roads and the communities located along them. Together, these programs established new avenues for heritage tourism and economic development along America’s historic routes, including the Lincoln Highway.

Photograph: This graphic was designed by Paul Kolsti for the Sacramento Bee to support the Federal Highway Act, encouraging infrastructure improvements, on April 28, 1991.

Reactivation of the LHA

1992 On October 31, 1992, the national Lincoln Highway Association was reactivated. The organization was established by Gregory M. Franzwa, who had formerly participated in the preservation of wagon trails in California and Oregon. Other participants included the author of The Lincoln Highway: Main Street Across America, Drake Hokanson, and Joyce and Bob Ausberger, who identified lost segments in Iowa and advocated for preservation by listing several resources on the National Register of Historic Places.

Photograph: The reactivated Lincoln Highway Association in Ogden, Iowa, October 31, 1992. Courtesy of Lincoln Highway News.

Designation as a National Scenic Byway

2000 In Illinois, the state chapter of the Lincoln Highway Association submitted the route for designation as a National Scenic Byway by the Federal Highway Administration. The Illinois segment of the Lincoln Highway, composed of 178.8 miles, is the first and only section to receive this designation in its entirety.

Photograph: "An Illinois Seedling Mile," undated. Courtesy of the Lincoln Highway Digital Image Collection at the University of Michigan Library.

701 Essington Road, Suite 100 Joliet, IL 60435 (844) 94-HCCVB (844-944-2282)