The Black Experience Along The Lincoln Highway

Crucial to the study of the Lincoln Highway are the voices that are not often heard in its telling. The Black experience of the Highway was historically dominated by systematic racism perpetuated by anti-Black legislation and a majority white media. Transcontinental travel, although a fun, novel, and progressive adventure for some, was a perilous and uncertain experience for Black travelers. This timeline will explore the Black experience along the Lincoln Highway, covering topics from auto culture to travel considerations for Black travelers. It will also include a study of historical racial violence and control along the highway route in Illinois. Studying these topics helps us to understand how place-based histories of racism have shaped inequality still experienced today.

Scroll down ↓

Jim Crow Era (c. 1877-1964)

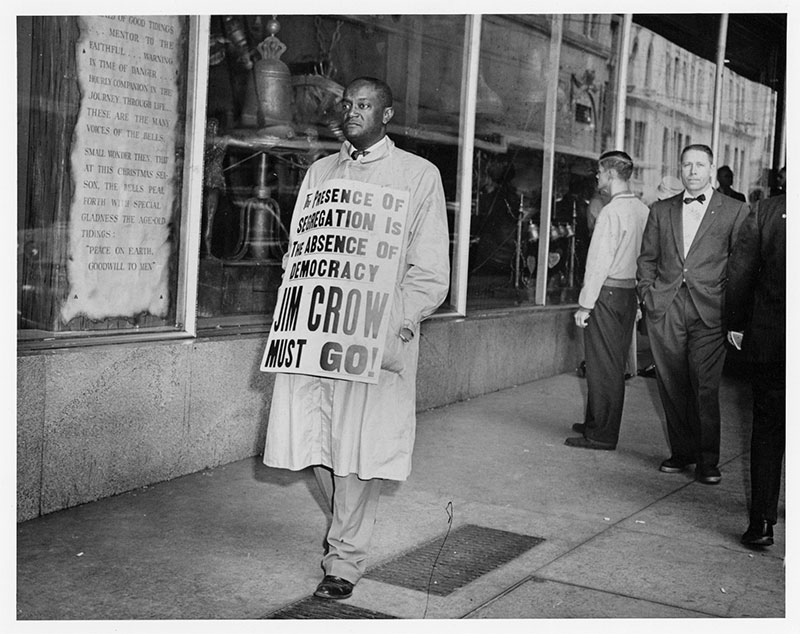

The genesis and growth of the Lincoln Highway (1913 to 1967) aligns with the violent period of American history known as the Jim Crow Era (c. 1870-1965). Jim Crow was a racial caste system that included a series of anti-Black laws and a day-to-day culture that legitimized anti-Black racism nationally, but most overwhelmingly in the southern United States.

Threats to Black lives and the dismissal of their humanity were rationalized with the following beliefs, as listed by the Jim Crow Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan:

- White people were superior to Black people in all important ways, including but not limited to intelligence, morality, and civilized behavior.

- Sexual relations between Black people and white people would produce a mongrel race which would destroy America.

- Treating Black people as equals would encourage interracial sexual unions. Any activity which suggested social equality encouraged interracial sexual relations.

- If necessary, violence must be used to keep Black people at the bottom of the racial hierarchy.

These disturbing beliefs were perpetuated in various ways to relegate Black people to second-class citizens, from segregated bathrooms, water fountains, and restaurants to the growth of the Klu Klux Klan, lynchings, and other forms of violent intimidation and murder supported by the law.

Photograph: Man Protesting in Atlanta, 1960 Atlanta University Robert W. Woodruff Library

The Great Migration (1910-1970)

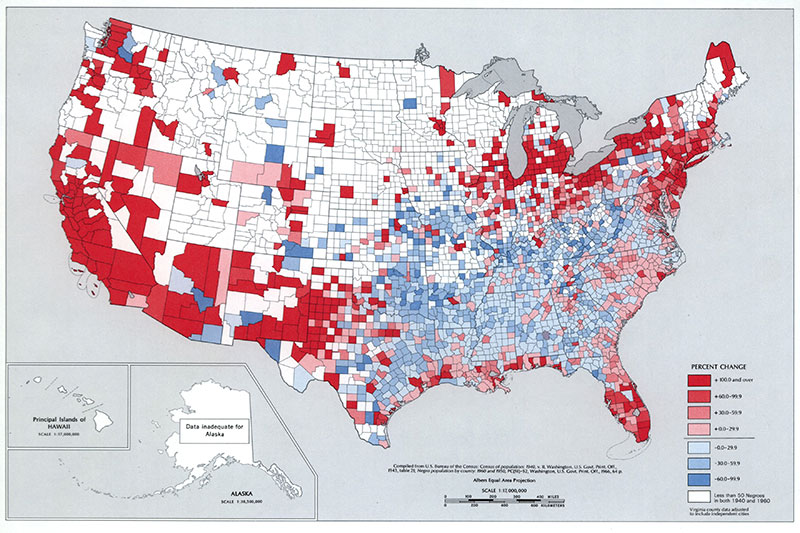

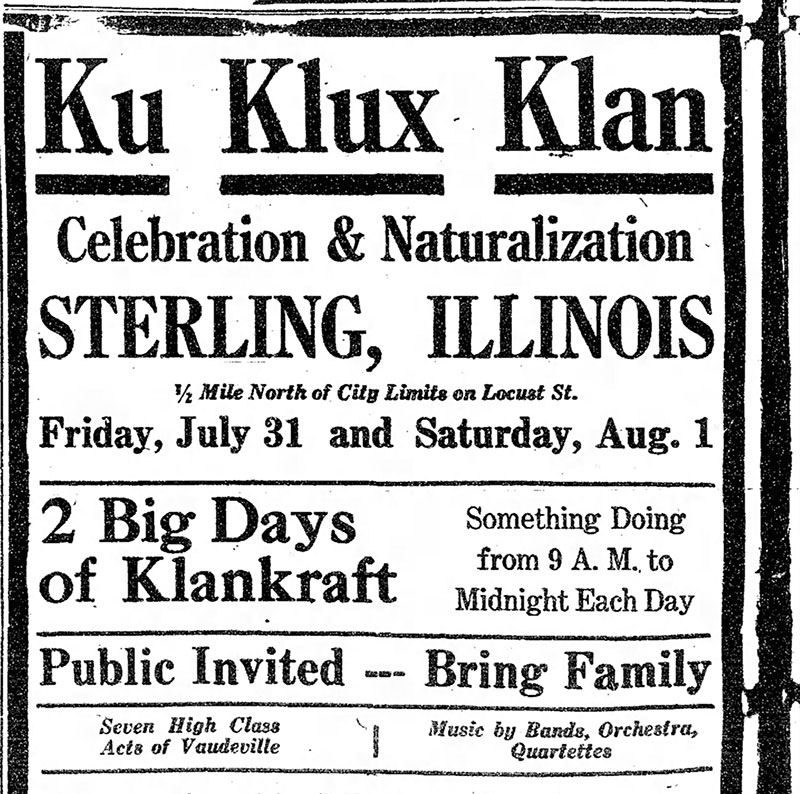

Between 1910 and 1970, over six million Black people migrated from the southern United States to large cities in the north and west, including Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. This period marked the beginning of the Great Migration. Individuals and families left their homes with the hope of better opportunities and to escape the violent and oppressive conditions of the southern states under the racially driven Jim Crow laws. However, reality fell far short for many as conditions were still repressive and segregated. Within Chicago, Blacks were restricted to renting in the Black Belt in white-owned housing that was often dilapidated, overcrowded, and typically more expensive than comparable housing in white areas. Racism continued to run rampant across the nation as hate groups, like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), grew in the 1920s all across the country, especially in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. Rural communities, as well as large municipalities, including Chicago, had active KKK groups.

With an influx of Black Americans to northern states coupled with the perpetuation of deliberate acts of discrimination, arriving Black Americans established new communities on the periphery of metropolitan areas. On the Lincoln Highway, one notable example is the community of Ford Heights, located near the Indiana border in southern Cook County.

Photograph: The map at the right identifies changes in the populations of Black Americans throughout the United States between 1940 and 1960. From the National Atlas of the USA, William T. Pecora, Under Secretary of Interior; W.A. Radlinski, Associate Director, U.S.G.S.; Arch C. Gerlach, Chief Geographer; and William B. Overstreet, Chief National Atlas Project.

Ford Heights

Non-indigenous settlement in the present-day area of Ford Heights began in 1848 with the arrival of European farmers who established onion fields and fruit orchards in Bloom Township. Based on available historic topographic maps, farmlands and prairie were subdivided into the “Park Addition” between 1924 and 1929. Acting together in 1924, 40 families successfully petitioned for electrical service. That same year, the main east-west road became a two-lane concrete highway designated U.S. Route 30 in 1926, which later became part of the Lincoln Highway system. That same year, the Park Addition was renamed East Chicago Heights, noting its location near Chicago and along the Tinley Moraine glacial ridge.

As the former farming community became more urbanized, its demographics shifted to welcome Black Americans who were relocating from the southern United States during the Great Migration. Early Black families in the community include Isabella and Simon Greenwood, as well as the family of Alberta Armstrong.

Greenwood and her husband, born into slavery, built a small house in the community in 1893. Alberta Armstrong became active in the community during the 1940s, organizing the women of the community to raise funds for a new fire truck and eventually establishing the East Chicago Heights Citizens Association in 1948. Armstrong went on to serve as the village clerk from at least 1951 to 1961.

Photograph: Alberta Armstrong at the Village Workers Club of East Chicago Heights; front row, extreme left. The Robbins Eagle, September 25, 1954.

Ford Heights, IL

The small village was officially incorporated in 1949 as East Chicago Heights. The population of the area grew with the arrival of a Ford Motor Company Stamping Plant located on the border between Chicago Heights and Ford Heights in 1956. The plant has served as the primary employer for the communities since its opening and currently produces auto body panels, employing 784 people.

The community reflected the growing population of auto workers and the need for a change in identity separate from Chicago Heights, which led to the name change to Ford Heights in 1987.

Today, the community reflects the challenges experienced by many majority-Black communities caused by societal racism: lack of funding, infrastructure maintenance, educational opportunities, and overall governmental neglect. The result is noted in the Ford Heights Strategic Plan of 2020, including population loss, a shrinking tax base, difficulties in attracting and retaining businesses, crumbling infrastructure systems, blighted neighborhoods, crime, and flooding.

Photograph: Chicago Stamping Plant at Ford Heights; Architectural Record, December 1961.

Sundown Towns

With the continuation of systematic racism during the Jim Crow era, predominantly considered to be limited to the southern United States, restrictions on Black Americans were simultaneously, quietly put into place across northern states. One of the most common practices in Illinois was the use of “Sundown laws" (c. 1890-1970).

Communities with these laws are now known as “Sundown Towns.” These laws enforced racial segregation by excluding non-white people from communities through the use of discriminatory laws, such as prohibiting Black Americans from staying overnight, intimidation and racial violence, typically proliferated by the presence of hate groups like the KKK, exclusionary real estate covenants, and actual “Sundown” signs which told “colored people” to leave by sundown. Along the Lincoln Highway, several communities had written and/or verbal “Sundown laws,” as well as active local chapters of the KKK during the early-to-mid-twentieth century, including Sterling, Ashton, and Dixon.

During the first two decades of the Lincoln Highway's existence, there was no map of towns with “Sundown laws,” making travel along the route particularly dangerous and unpredictable for Black travelers. Other considerations for Black travelers included whether they would be permitted in essential business establishments along the highway, such as restrooms, hotels, campsites, restaurants, and service stations.

Photograph: An advertisement for a public festival celebrating the Ku Klux Klan in Sterling, Illinois. From the Sterling Daily Gazette, July 25, 1925.

Travel Guides for Black Americans

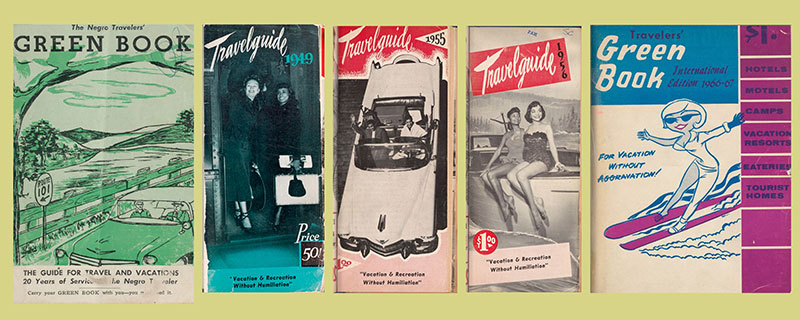

With the growing availability of cars, new highways, and the advent of auto culture, the age of the automobile was rapidly growing in the 1920s. However accessible it became for some, segregation, harassment, and racial violence against Black Americans were still widely prevalent across the country. In the 1930s, several Black-owned travel book companies emerged with a shared goal: to provide safety and recreation for Black travelers on the road.

The guides shared safety tips and civil rights laws, as well as the locations of businesses that welcomed Black customers. These guides were published in response to attacks on Black tourists by racist, violent citizens as well as police officers supporting Jim Crow laws or their prejudice.

Without the guides, Black travelers in a new city would not know which restrooms, hotels, restaurants, gas stations, and shops would be safe to patronize. If a town had no listings, the likelihood of it being a hostile environment was high.

The most well-known guide is the Negro Motorist Green Book, also known as the Green Book. Black businessman Victor H. Green started the publication in 1936 to facilitate “vacation and recreation without humiliation.” Other publications included Hackley & Harrison's Travelers Guide for Colored Travelers (1930), Afro-American's Travel Guide (1939), Travelguide (1946), Go: Guide to Pleasant Motoring (1952-1959), and The Black American Travel Guide (1971).

Photographs: New York Public Library Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Illinois Green Book sites on the Lincoln Highway

On the Lincoln Highway in Illinois, the Green Book and Travelguide published advertisements and listings for businesses in Fulton, Sterling, Joliet, and Aurora. The majority of listings in Illinois, as a whole, were in Chicago, which is only connected to the Lincoln Highway via feeder routes. It is worth noting that the listings in the smaller municipalities are primarily present after 1945, when Sundown laws and associated activities became less widespread in Northern Illinois.

Green Book lists the Twin Oaks Tourist Camp as a hotel destination between Morrison and Fulton, Illinois. The camp was a motor-in camp, featuring quaint cabins, fire rings, and areas for pitching tents.

Photograph: Twin Oaks Tourist Park postcard. Published in Images of America The Lincoln Highway Across Illinois by David Belden and Christine O'Brien.

Illinois Travelguide Sites on the Lincoln Highway

Travelguide as a whole has more listings along the Lincoln Highway in Illinois. Beginning in 1946, it lists Sterling, Illinois, with three lodgings within the homes of Grace Coleman (11 Avenue G), Princess Jackson (1102 Avenue J), and Bessie Siex at an unlisted number on the Lincoln Highway.

In 1956, the YMCA of Joliet was listed in Travelguide (311 S. Chicago Street). The next year, Joliet features McGill’s Lounge at 629 Patterson Road.

In 1962-63, North Aurora had listings for two hotels in the Travelguide, Hilton Inn (230 S. Lincoln Way) and Holiday Inn (311 S. Lincoln Way). It also lists the motor club, American Auto Association (AAA) at 217 Main Street.

Photograph: The Hilton Inn at 230 S. Lincoln Way, North Aurora, Illinois as pictured in c. 1970 in a postcard. The back of the postcard reads: "This aerial view shows the Hilton Inn's spacious layout. For Reservations: TWINOAKS 7-0451"

Auto Culture in the Post-war Era

Following the end of World War II, the country experienced booming economic growth, coupled with the end of wartime material shortages, which spurred the continued growth of the auto industry and culture.

Flashy advertisements in periodicals and on the newly widespread home television sets promoted an American image of affluence based on material goods. The method of choice for flaunting this image was often what car you drove. Furthermore, the new Eisenhower-era Interstate Highway System made driving an accessible pastime. Soon after, many businesses formed or rebranded to serve drivers, including drive-in fast food restaurants, drive-in movie theaters, and automatic car washes, among others. The result was an upward-trending auto culture, which was most prevalent between 1950 and 1960.

Photograph: Advertisement for the Lark Studebaker; Ebony Magazine, February 1960.

Auto Culture in the Post-war Era

During the post-war era (c. 1945-1968), auto sales reached their peak in 1955, with 7.9 million American cars sold. Three American car companies, General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler, competed fiercely to design the newest, most modern – or even futuristic – styles for consumers. Companies created both high-end and affordable models, which created demand across all demographics.

In 1957, Chrysler’s Plymouth division published the first print advertisement featuring a Black female model. Soon after, Chrysler purchased recurring advertising space in Ebony Magazine – a prominent periodical chronicling Black life since 1945. The Studebaker company followed suit, publishing ads for their Lark model in Ebony. These ads featured happy families and beautiful models, depicting the American dream with Black joy.

Photograph: The first auto advertisement featuring a Black female model, Chrysler Plymouth, 1957. Detroit Historical Society.

Travel in the Civil Rights Era

The decline of the Lincoln Highway, following the advent of the Interstate Highway System, coincided with the end of legal segregation in the mid-1960s.

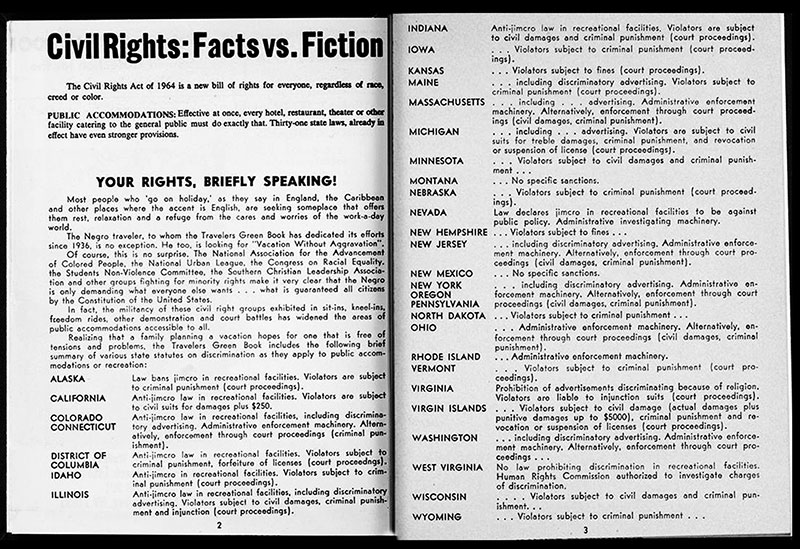

Despite travel guides and the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, safety during travel remained unpredictable for Black people. While the Civil Rights Act was established nationally, each state had statutes that made protections may vary wildly. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act, travel guides became obsolete as interstate travel was desegregated by outlawing discrimination in public accommodations and transportation. As a result, Black travelers could now legally patronize all businesses, and an increase in the availability of Black-owned businesses, including travel and tourism agencies, further facilitated this access. However, in their final issues, the Green Book and Travelguide began publishing state-by-state summaries of civil rights so travelers could navigate the legal landscape and challenges of ongoing segregation and racial discrimination.

Photograph: Travel Laws and Civil Rights, Travelers Green Book, 1966 (two years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964).

701 Essington Road, Suite 100 Joliet, IL 60435 (844) 94-HCCVB (844-944-2282)