The History and Impact of Native Americans on The Lincoln Highway

The land now occupied by the Lincoln Highway is located across the unceded ancestral lands of the Illiniwek (Illini or Illinois Confederation), the Council of the Three Fires, including the Prairie Band of the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Ottawa, and the Ho-Chunk, who inhabited these lands for thousands of years as the rich forests, prairies, and rivers provided the hunting and fishing grounds for the First Nations.

Furthermore, the recorded history of this land includes early examples of the Middle Woodland Period or Hopewell Culture (as early as 100 B.C.E.) at Albany Mounds State Historic Park near Fulton, Illinois. This period is followed by the Mississippian Culture (900 C.E. to 1500 C.E.), which is divided into two traditional “lifeways,” encompassing the culture, traditions, teachings, and histories passed down between generations. The lifeways of fishers and wild rice gatherers resided near the Great Lakes, while the prairie landscapes of inland Illinois provided for the lifeways of farming chiefdoms. The many rivers of Illinois allowed for thriving, centuries-long trading traditions between tribes. Often, tribes established seasonal movement patterns, such as hunting one area in the summer and wintering in another.

The following slides will only begin to explore the history of Indigenous people in Illinois, specifically their legacy and impact on the formation of the Lincoln Highway. Travelers are encouraged to visit the sites mentioned in this section to learn more about how Native Americans have shaped our communities and lives.

Scroll down ↓

Native American Trails and the Lincoln Highway

The route of the Lincoln Highway is directly related to the establishment of ancient Native American trails across the nation, which were forged with the topography of the land as migratory paths between trading posts, waterways, and hunting grounds.

Early in the history of the Lincoln Highway, it was determined that the route would follow previously established roads, many of which originated as Native American trails and later became stagecoach routes and pioneer trails as westward expansion took hold in the early to mid-nineteenth century.

In Illinois, the Lincoln Highway follows two prominent trails in the eastern part of the state - the Sauk Trail and the Vincennes Trace.

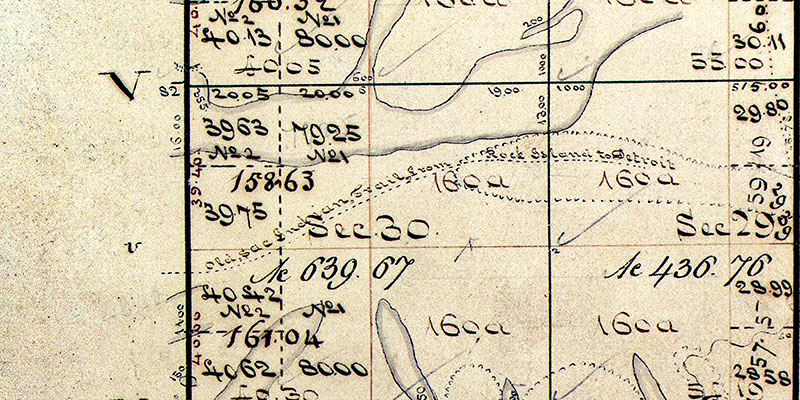

Photograph: The crossing of the Sauk Trail and the Vincennes Trace located in Section 32 at the bottom of the image. U.S. Surveyor Generals Township Plats of Illinois, 1839..

The Sauk Trail

In Illinois, the first generation route of the Lincoln Highway enters the state on the Sauk Trail from Dyer, Indiana, where it continues westward to South Chicago Heights.

The Sauk Trail was a prominent Native American trail spanning present-day Illinois, Indiana, and Michigan. It is believed that the trail began at the Mississippi River in present-day Rock Island, Illinois, and ran eastward along the Illinois River before reaching Chicago and its eastern terminus at Detroit. Later in the trail’s history, it served as a significant thoroughfare along the Underground Railroad, extending from Haven’s Old Brick Tavern in New Lenox, Illinois, to Detroit, where enslaved people safely entered Canada. Of the estimated 45,000 slaves who made it to Canada, approximately 4,500 are believed to have traveled along the Sauk Trail. During the nineteenth century, the Sauk Trail was also a major stagecoach route that brought pioneers westward and served as a catalyst for settlement in Illinois.

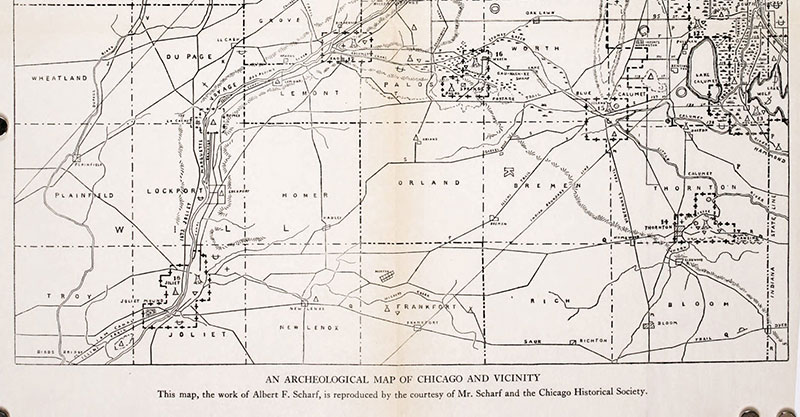

Photograph: The bottom of the image illustrates the Sauk Trail as it crosses near Sauk Village, South Chicago Heights, Frankfort, New Lenox, and Joliet. The map is the Albert F. Scharf Indian Trails and Villages of Chicago, 1900.

The Vincennes Trace

At South Chicago Heights, the Sauk Trail (Lincoln Highway) crosses the Vincennes Trace. The Vincennes Trace, later known as Hubbard’s Trace, was a significant trail spanning Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois formed by millions of migrating bison. The “Trace” crossed the Ohio River near the Falls of the Ohio and continued northwest to the Wabash River, near present-day Vincennes, Indiana, before it crossed into Illinois. The trail was also used by Native Americans, and later by European traders and American pioneers. After a major crossing at the Wabash River, the “Trace” split into separate trails that headed westward through Illinois to the Mississippi River or north to Chicago. In Chicago, the “Trace” became known as Vincennes Avenue, with portions becoming State Street. The “Trace” was the first designated state road in Illinois in 1834.

The portion of the trail through South Chicago Heights was incorporated into the original route of the Lincoln Highway and later into the Dixie Highway in 1915.

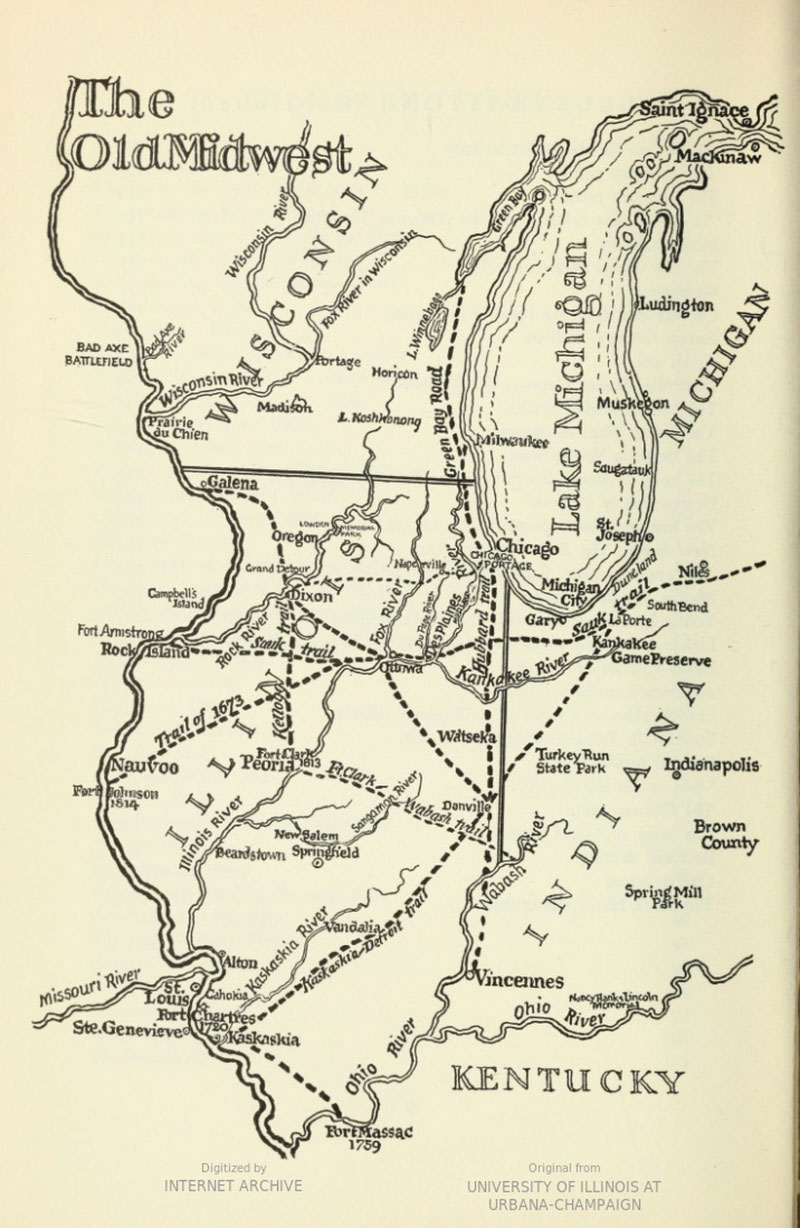

Map: Episodes in the Lives of Some Individuals who Helped Shape the Growth of our Midwest, Ralph Fletcher Seymour, 1954.

Forced Removal of Native Americans

Both the Sauk Trail and Vincennes Trace were utilized in the colonization of North America, disrupting the migratory patterns, trading traditions, living places, and hunting grounds of Native Americans beginning in the 1600s.

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, European explorers first documented the presence of the Illini and recorded approximately 10,000 Native people. This number quickly dwindled over the next century. Seven Illini confederation tribes, the Chepoussa, Chinkoa, Coiracoentanon, Espeminkia, Maroa, Moingwena, and Tapouara, disappeared due to the fur trade conflicts of the Beaver Wars. The Beaver War conflicts lasted most of the century, ending in the destruction of several tribal confederacies and the displacement of eastern tribes.

By the end of the eighteenth century, the Revolutionary War (1775-1783) was followed by a series of events that catalyzed Westward Expansion. First, the Treaty of 1804 ceded over 50 million acres of the ancestral lands of the Sauk and Meskwaki (Fox) tribes to the United States government in present-day Missouri, Illinois, and Wisconsin, with the guarantee that the tribes would be permitted to live, hunt, and farm on these lands. Next, following the War of 1812, the United States government established military outposts to serve new western states and territories, including present-day Wisconsin and the northeastern region of Illinois. In 1816, the Treaty of St. Louis ceded nearly 200 square miles of land from the Ottawa, Chippewa, and Potawatomi to establish a 20-mile corridor of “safe passage” for white men and women between the Illinois River and Lake Michigan that includes present-day Chicago. This corridor, known as the Indian Boundary Line, meant that Native people were not allowed to enter the boundary to access waterways, hunting grounds, and existing villages. The southern boundary crosses the Lincoln Highway in Frankfort, Illinois.

The southern boundary crosses the Lincoln Highway in Frankfort, Illinois.

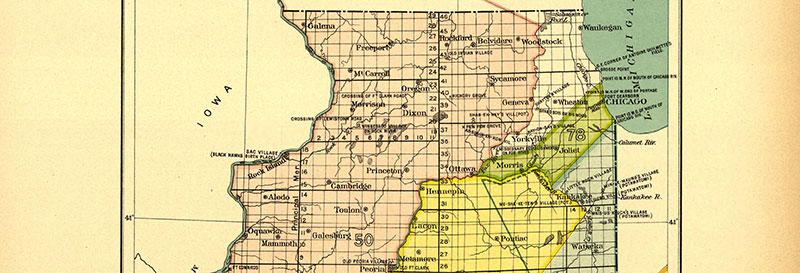

Map: The Indian Boundary Line corridor is indicated by the bright green color and the number 78. Indian Land Cessions in the United States, Charles Royce, Cyrus Thomas. Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, 1896.

Forced Removal of Native Americans

After the State of Illinois was established in 1818, a subsequent series of additional treaties over the next 15 years caused the continued forced removal of Native Americans. For example, the Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien, signed in 1829, was one of 12 major treaties that significantly reduced the population of the Potawatomi people and forced them to relinquish nearly 3.5 million acres of tribal land.

Native Americans who tried to continue their way of life were prevented from entering their land by a huge influx of white settlement, resulting in the loss of available game, access to waterways, and decreased land for harvest and cultivation. Native people were forced to the lands west of the Mississippi River because of these factors. In 1830, the Indian Removal Act officially set the stage for the complete removal of Native people from Illinois.

The implementation of the act was delayed while the United States government focused on the Sauk tribe at Rock Island, who had denounced the 1804 treaty that stipulated their removal from western Illinois. The events that followed are commonly known as the Black Hawk War of 1832. Roughly 800 Sauks, led by their band leader and warrior, Black Hawk, chose to stay on their land and resist the United States’ westward expansion. They were determined to protect Saukenuk, but when their group returned to the village after their winter hunts in 1829-1831, they found it increasingly occupied by white squatters. Their homes were claimed by white settlers, their corn hills used as storage for wagons, and the bones of their ancestors were disturbed and laid bare upon the ground by the plow.

After a series of bloody battles, the cause of Black Hawk was lost, and his allied tribe was scattered across Oklahoma and Iowa.

Their territory extended from Green Bay, beyond Lake Winnebago, to the Wisconsin River and the Rock River in Illinois, approximately eight-and-a-half million acres as recognized in the Treaty of 1825. The area served as a center for the Indigenous people to gather, trade, and maintain kinship ties.

Simultaneously, the Ho-Chunk were forcibly removed from Wisconsin and Illinois between 1832 and 1874 as the U.S. government and non-native settlements continuously pushed them north and west into present-day Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska in the pursuit of lead mining and agriculture. The Ho-Chunk refused to live on the increasingly infertile lands away from their abundant homelands in Wisconsin. Many returned to Wisconsin and joined those who refused to leave to purchase back their land in their ancestral home under the 1862 Homestead Act. This act of strength and resilience led to the passage of a new national law, the Indian Homestead Act of 1875, and ultimately resulted in a nation of over 10,000 citizens today.

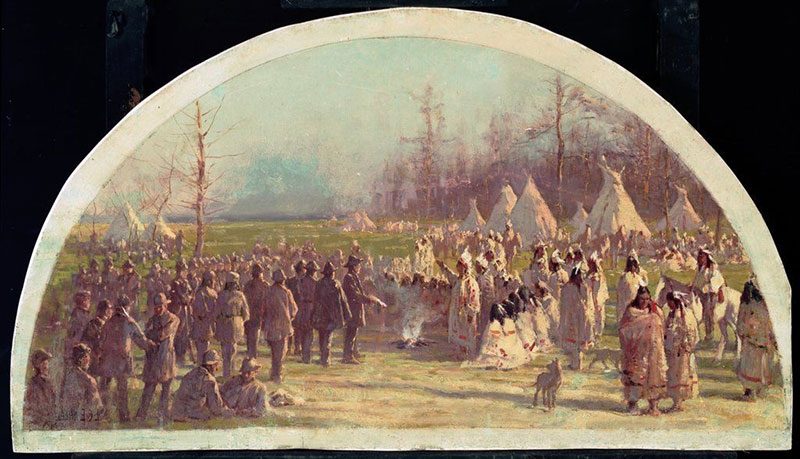

Photograph: The Last Council of the Potawatomie, 1833. Lawrence C. Earle, Chicago History Museum, 1904.

Westward Expansion and the Depiction of Native Americans

During Westward Expansion, the cultural phenomenon of romanticizing the West, its wilderness, storm-beaten landscapes, virgin soils, and perilous exploration, spread throughout the nation. In art, movements such as the Rocky Mountain School shared this idea visually. In the written word, stories written by white authors, such as the Little House books by Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Wau-Bun: The “Early Day” of the North-west by Chicagoan Juliette Magill Kinzie often described the West with tales of dangerous encounters with Native Americans and their travels in “Indian Territory.”

These naive depictions were further proliferated in media and marketing, such as the “Cigar Store Indian” or the “Indian Maiden,” which stereotyped Native people through the uncultured use of ethnic imagery in advertising. Often, the “American Indian” is depicted with "red" skin in a feather headdress, with fringed loincloths, and covered in tattoos and face paintings. However, this type of dress only represents a few tribes, such as the Lakota and Cheyenne, out of hundreds that once called the lands, now known as the United States, home.

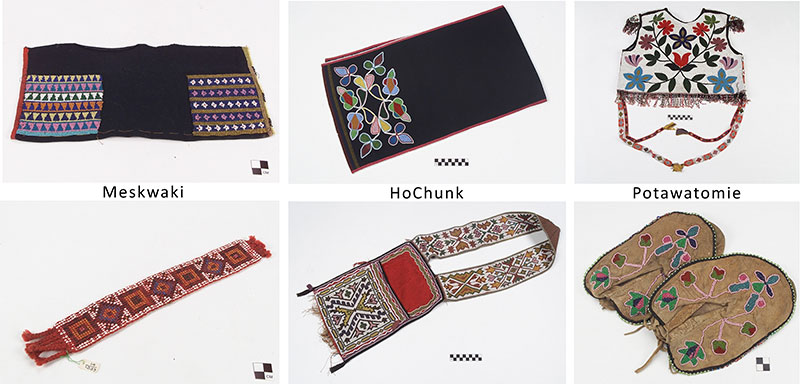

In Northern Illinois, the typical dress of Native people often reflected the fur trading societies of the Great Lakes region, including fur, leather, and cloth coverings. Jewelry consisted of copper as the primary metal, often featuring ribbonwork or silk appliqué. Each tribe in Illinois has its history of clothing and ceremonial costuming. For example, the Potawatomi male costume included colorful head shawls and tanned deerskin pants, while women wore sleeveless deerskin dresses.

Photographs: Collection items from the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian.

Depictions of Native Americans on the Lincoln Highway

The image of Native Americans is often used by non-native groups and people in stereotypical ways in order to capitalize, advertise, make fun of, or indicate wildness. Common stereotypical depictions include advertisements, Halloween costumes, sports mascots, fashion trends, and characters in pop culture. While many of these usages often seem harmless, the depictions are often disrespectful and indicate ignorance about the culture they are referencing.

As well as images, language can be used in stereotypical, disrespectful ways against Native Americans. Until recent decades, racist and inaccurate linguistic features, such as adding “-um” at the end of verbs or using “How” as a greeting, were commonly used as a comedic language called “Hollywood Injun English” or “Tonto Talk” in advertisements, television shows, and movies.

On the Illinois section of the Lincoln Highway, many examples of stereotypical depictions have been removed, but some remain, including the Sauk Trail Car Wash sign in Sauk Village, Illinois. In this example, the sign depicts a figure with exaggerated facial features and crossed eyes. Another example is the non-extant Good Will Used Cars in DeKalb, which featured a large teepee as a showroom.

Photograph by Mike Eckman, 2018.

Native American Sites Along the Lincoln Highway

Across Illinois, the Lincoln Highway connects several historic sites associated with Native American history.

Nine miles south of Fulton, the western terminus for the highway in Illinois, is the Albany Mounds State Historic Site in Albany, Illinois. The Albany Mounds are an archaeological site comprising at least 39 extant burial grounds associated with the Middle Woodland Period (Hopewell Culture), dating back to as early as 200 B.C.E.

Located on the Rock River, 12 miles south of Morrison, Illinois, in Whiteside County, is Prophetstown State Park. This park is the historic location of the village of Wa-bo-kie-shiek (White Cloud), named after the Ho-Chunk and Sauk man (originally born as Poweshiek) who served as an advisor to Chief Black Hawk during the Black Hawk War. On May 10, 1832, as part of the Black Hawk War, the Illinois state militia, commanded by General Samuel Whiteside, attacked and destroyed the village. Today, the site of the attack and the memorial to Wa-bo-kie-shiek can be visited in the State Park.

Native American Reservations

Following the Indian Relocation Act of 1830 and the Black Hawk War of 1832, the State of Illinois established several small reservations for Native Americans. In some cases, this was due to previous treaty agreements or good relationships with tribal leaders. In other cases, parcels of land were granted to individual Native American farmers, traders, and hunters.

“Indian Reservations” were of multiple types. The largest are created by the Federal government to designate permanent homelands for tribes. Very rarely are these the ancestral homelands of the tribe, and the residents were forced to relocate. The State can also designate smaller reservations, often for individual Native American families or persons, on their ancestral homelands.

In present-day communities along the Lincoln Highway, reservations were established in Frankfort, Oswego, Aurora, and DeKalb. The following includes only a few identified examples of reservations, but many others have been lost to time or were not directly related to the Lincoln Highway area.

In Frankfort Township, five small reservations were established by the second article of the Treaty of Chicago, ratified on January 1, 1833. They include one each for Man-i-to-qua and his wife, one for Archange Pettier, and one each for Joseph Framboise and his wife, Theresa. Today, the former land associated with the Man-i-to-qua Reserve is the Camp Manitoqua Retreat Center.

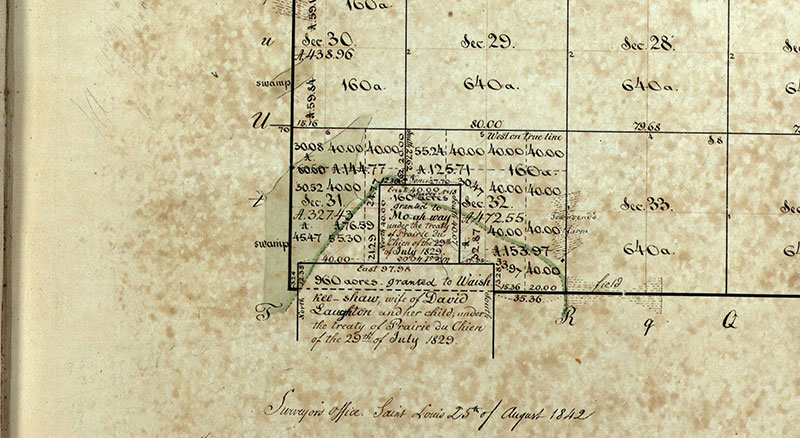

In Oswego, the present-day road “Reservation Road” indicates the history of Native American reservations in the village. The Treaty of Prairie du Chien 1829 granted at least two reservations in Oswego. The first is the Mo-ah-way reservation, consisting of one-quarter of Sections 31 and 32. The History of Kendall County (1877) indicates that the surrounding area was originally an entire Native American village. Another reservation, just south of Mo-ah-way, was granted to Waish-kee-shaw, a Native American woman who was married to a White man, David Lawton.

Near Aurora was a five-mile reservation used as hunting grounds by the Potawatomi, led by Chief Waubonsie and his tribal members. This land was used seasonally by the Potawatomi to hunt, and their homeland would have been elsewhere.

DeKalb County contains the ancestral homelands of Chief Shab-eh-nay (Shabbona). See the final slide for the history of this land as a reservation and recent news regarding its return to the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.

Map: Surveyed "Indian Reservations" in Oswego, Kendall County. U.S. Surveyor General Federal Township Plats, 1842.

Federally Recognized Tribal Nations in Illinois

The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation historically relinquished 28 million acres of their land to the United States government as well as the State of Illinois. However, they did not relinquish 1,280 acres of land in present-day DeKalb County. This land, Chief Shab-en-nay’s (or Shabbona) home reservation, was stolen by the United States government and illegally auctioned off in 1849, while he was visiting the tribe at the Kansas reservation, where they were forced to relocate to in the early 1830s.

In 2024, after 175 years of activism and legal action by the Potawatomi, the State of Illinois acknowledged this injustice by designating the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation the first federally recognized tribe in Illinois. In addition, 130 acres of Shab-en-nay’s home reservation land was returned to the tribe. The next year, in January 2025, an additional 1,500 acres of land, including Shabbona Lake State Park in DeKalb, Illinois, was transferred to the tribe under Senate Bill 867, signed into law by Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker. The law marks the point in history in which Illinois conceded that the seizure of the land in 1849 was illegal.

Photograph: Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation (PBPN) insignia with the Illinois homeland outlined. Courtesy of the PBPN.

701 Essington Road, Suite 100 Joliet, IL 60435 (844) 94-HCCVB (844-944-2282)