Women on the Lincoln Highway

Undoubtedly, the role of women was influential in the creation of the Lincoln Highway. The movement to create an “ocean-to-ocean boulevard” was in lock-step with a larger movement for equal rights for women during the turn of the twentieth century. The Lincoln Highway was vastly supported by leaders of national suffrage movements as it served as a symbol of progress into the modern age.

Individuals and women’s groups across the country raised awareness and crucial funding for the highway in the early years. During the construction of the highway, women played a physical role in the actualization of the highway's vision and design. Women's suffrage groups formed committees dedicated to the landscape design of the highway across the country, with each state designed to feature characteristics specific to that location. Other women supported the highway with adventurous travels across its length, alone. Promotions for these journeys generated significant media buzz for the Highway, as they documented some of the first examples of women traveling independently, despite societal norms that viewed travel as a male-only activity.

Dive deeper into the stories of some women who influenced the Lincoln Highway.

Scroll down ↓

“Probably there is not a woman in this audience who, even in her innermost thought, believes that the Lincoln Highway can be built, beautified, and operated in its superlativeness without the aid of women.”

- Mary Hardy, Historian and Author of "The Lincoln Highway and its Possibilities," 1915.

Alice Ramsey

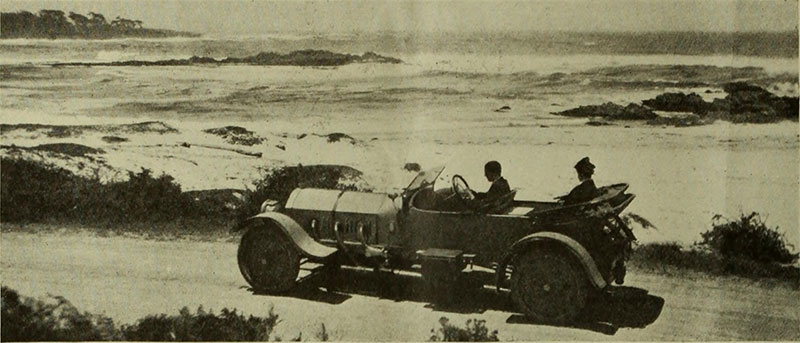

In June 1909, Alice Ramsey, her friend Hermine Jahns, and her sisters-in-law Nettie Powell and Margaret Atwood set off on a 59-day automobile journey from 1930 Broadway, New York City, to the Pacific Ocean in San Francisco. The journey would make Alice the first woman to drive a car across the continent. In 1961, Ramsey wrote her memoir Veil, Duster, and Tire Iron, which recounts their experiences. While en route, the women encountered roads that were either almost exclusively dusty or muddy. Other obstacles included five-foot-wide potholes and confusing directions from Auto Blue Books that relied on landmarks rather than road names. The women were in charge of their auto repair and carried a complete mechanic’s toolbox with them.

In 2005, Gregory Franzwa, the President of the Lincoln Highway Association, discovered that the journey Alice recounted in her memoir included routes that would be utilized by the Lincoln Highway four years later. After studying her book, he republished it and included an annotation illustrating her use of the future Lincoln Highway in Alice’s Drive: Republishing Veil, Duster, and Tire Iron.

“You don’t have any pillows?" "Pillow?" I echoed with perhaps a touch of scorn, “If one of us needs a pillow, I guess she’ll have to board a train to the next stop!” This journey demanded a sturdy crew!

- Alice Ramsey in Veil, Duster, and Tire Iron, 1961.

Photograph: Alice Ramsey and Passengers in her Maxwell, 1909. Courtesy of the National Automotive History Collection.

Mary C. C. Bradford

National Suffrage leader Mary C. C. Bradford was a Colorado educator who was the first woman in the United States to be nominated for a constitutional elective office. Bradford participated in the suffrage movement in Colorado, leading to the referendum that granted women the right to vote in Colorado in 1893, 26 years prior to the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which granted women the right to vote nationally.

Bradford believed in the power of education as a tool to promote citizenship and patriotism. Because of this, she supported the Lincoln Highway as a memorial to President Abraham Lincoln that would inspire the youth of America.

In 1911, Bradford “Urged the Lincoln Highway” in national periodicals. Knowing first-hand the power of collective women, she called upon the women of the nation to support the highway as a dedication to Lincoln’s memory. Because of her work, women took up the charge of beautifying, promoting, and funding the Lincoln Highway.

Photograph: Ratification of the 19th Amendment in Colorado, 1919. Mary C.C. Bradford is seated at the right. Library of Congress.

DeKalb Women’s Club

In 1912, the DeKalb Women’s Club (est. 1865) purchased a 10-acre tract of land above the Kishwaukee River near Northern Illinois University in DeKalb to establish a city park. The land was owned by Annie I. Glidden and Bertha and Samuel Bradt who sold the property for half price with a contract to pay in full by 1917. On May 1, 1917, they met their goal and donated the land to the City of DeKalb as a public park known as Annie’s Woods. The event was marked at the center of the entrance drive by a stone pillar with a central monument plaque. Also located at the main entrance are stone walls that flank the drive. In 1923, the Kiwanis Club of DeKalb donated and constructed the walls and a shelter house.

The park has served as the base for Chautauqua cultural events, concerts, and talks, as well as a campground for Lincoln Highway travelers. These camps were critical sites along the Lincoln Highway between the 1910s and 1950s. The camps served as inexpensive or free rest stops for travelers before the advent of the motor lodge or motel.

The park was named after Annie Glidden, a member of the DeKalb Women’s Club and the niece of famous DeKalb inventor and farmer Joseph Glidden, who invented an improved, mass-produced barbed wire in 1873. As a result, Annie was bequeathed a fortune at her uncle’s death in 1906. However, Annie herself was an award-winning farmer, a scholar, and an industrious personality. She made a lasting impact on DeKalb through her merit, work, and philanthropy. Included in her merits and accolades are attending Cornell University for Agriculture, farming an abundant yield of asparagus and corn crops, and establishing the Library Whist Club (a weekly, members-only card game that generated funds for the library).

Photograph: DeKalb tourist campgrounds, DeKalb, Illinois, undated. Courtesy of the University of Michigan Library.

Women’s Rights at the Turn of the Twentieth Century

At the turn of the twentieth century, women remained prohibited from small activities like wearing pants or faced societal disapproval for traveling without a man, to more significant limitations, including holding public office or the right to vote. In Illinois, women’s suffrage movements began in the 1860s. However, it would be several years until the first statute extending women’s rights was passed, allowing women to run for any school office in 1873. It would not be until 1891, though, that women were allowed to vote for school officers, the first voting right secured in the state.

With the continued work of several advocacy organizations, including the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, the Illinois Federation of Women's Clubs, and the Chicago Political Equality League, discussed later in this section, women in Illinois secured the right to vote for president in 1913, making Illinois the first state east of the Mississippi River to give women the right to vote for President.

Full women's suffrage in Illinois, including the right to vote for state and federal legislators, was not realized until the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

Photograph: Governor Edward F. Dunne signs the Suffrage Bill in Illinois on June 26, 1913. Courtesy of The Digital Research Library of the Illinois History Journal.

Chicago Political Equality League

In 1914, suffragist women from the Chicago Political Equality League piled in cars and drove along the Chicago feeder route to the Lincoln Highway in Chicago Heights. They were equipped with banners, horns, ladders, brushes, buckets, and painted signs along the route. Using sunflower yellow paint, a primary color associated with the suffrage movement, they climbed up posts and used stencils to write “To Lincoln Highway.” The women were led by the well-known author and Chicago suffragist Harriett Taylor Treadwell, president of both the League and the Illinois Women’s Legislative Congress.

They aimed not only to signal the route and celebrate the Lincoln Highway, but also to promote their cause: Equal Rights for Women. The highway symbolized progress into the modern age, which aligned with their vision of a more equitable future.

Photograph: The 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, was ratified in 1920. In August of that year, a Chicago suffrage group paraded through Chicago urging women to register to vote in their first election. League of Women Voters members are, left to right, Mrs. J.N. McGraw, Mrs. G.N. Payson, Mrs. Charles S. Eaton, Mrs. E.F. Bemis, Mrs. A.N. Schweizer, Mrs. Ida Strawn Randall, trumpeter Helen Hamilton and Billie Frees. Photograph courtesy of The Chicago Tribune.

Emily Post

Author Emily Post is best known for her prolific writings as the authority on social graces. However, she did not write her bestseller Etiquette (1922) until her 50s. Her writing career began in the late 1890s, when she supported herself and her two small children after a tumultuous, highly publicized divorce. This event served as a turning point for Emily, who was raised in the high society of Baltimore and New York City in the 1870s and 1880s, a time when divorce was frowned upon. By entering the workforce as a divorced woman, Emily broke with societal expectations of women in the upper echelon at the turn of the century.

Emily wrote for several periodicals, utilizing her New York finishing school writing skills, combined with an authoritative yet comedic style. In 1914, she was offered a recurring article in Collier's Weekly to document a motorcar journey from New York City to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915. Emily, her son Edwin Post, Jr., and her cousin Alice Beadleston took the journey without a chauffeur or mechanic. They used the roads that were rumored to be the best, including a section of the new and highly publicized Lincoln Highway.

In DeKalb and Ogle Counties, Illinois, Emily approached the Lincoln Highway, finding it less improved than was rumored. In her later novelization of the journey, By Motor to the Golden Gate (1916), she tells the story in a chapter titled: “MUD!” The section of highway west of DeKalb, which had not been paved yet, crossed Malta, Creston, and Rochelle. After the publication of Post’s account, officials in Rochelle were embarrassed by the national publicity and pledged to install a drainage system. They also considered paving the three-mile stretch west of the city, which was known as the worst road within 100 miles of Chicago.

"But, you see, San Francisco is where I am going. Do you know which route is, if you prefer it, the least bad!" "Oh, I see." He looked sorry, "Of course, if you must cross the continent… there is the Lincoln Highway!"

- Emily Post in By Motor to the Golden Gate Bridge, 1916.

Photograph: Emily Post driving along the Pacific Ocean between Los Angeles and San Francisco. The original source is unknown.

Anita King

In 1915, Paramount Studio actress Anita King set off on a solo adventure from San Francisco to New York City on the Lincoln Highway. Anita set the goal of crossing the country in 25 days, though it would take 49 days to make the journey due to several promotional stops. With her, she only brought a small suitcase, a shotgun, and her beloved bulldog. This created a media frenzy, with reporters meeting her in every major city. A Pomona, California reporter said, “When she looks one square in the eye and says with a quiet smile, ‘Yes, I’m going to drive across the continent alone,’ that settles it. You know she will.” Although many doubted her, Anita was confident in herself and her abilities, claiming that she would be unsafe or break down. She held her ground and completed the journey in a triumphant celebration, becoming the first woman to drive solo across the nation.

“There was [a] man and his wife who stopped a few moments to talk to me while I was resting. He became very insulting and called me a liar. Well, I beat them into the next town and when they arrived I had him arrested!”

- Anita King, Omaha Daily News, Sep 21, 1915.

Photograph: Anita King on the Lincoln Highway. The original source is unknown.

Arché club

In 1916, this public fountain on the Lincoln Highway was donated by the Arché Club of Chicago, a women's group that supported the arts. The fountain marks the location where the Lincoln and Dixie Highways intersect in Chicago Heights, Illinois. The intersection is significant as the intersection of the Sauk Trail and the Vincennes Trace, which were partially utilized as the route for the Lincoln Highway and Dixie Highway, respectively. Both routes were forged by several Indigenous tribes over centuries as migratory trails. In 1834, the Vincennes Trace was established as Illinois' first official state road, connecting Vincennes and Chicago. To honor this history, the Arché Club commissioned the fountain, which was designed by sculptor George E. Ganiere, following guidelines created by the club members. The Arché Fountain is still on view at the highway crossroads in Alex Lopez Park.

General Federation of Women's Clubs

During the planning phase for the Lincoln Highway, women played a pivotal role as visionaries in the landscape design. Groups of women across the nation who were part of the General Federation of Women’s Clubs supported the highway, forming Lincoln Highway Beautification Committees.

The stalwart Illinois chapter planned the first planting for the highway along the Seedling Mile in Malta, Illinois. The group hired Professor Wilhelm Tyler Miller of the University of Illinois, known as “the world's greatest landscape gardener.” Miller and a group of architects from the American Institute of Architects’ Lincoln Highway Committee investigated and created plans for “architectural perfectness” in the design of the road and its landscaping.

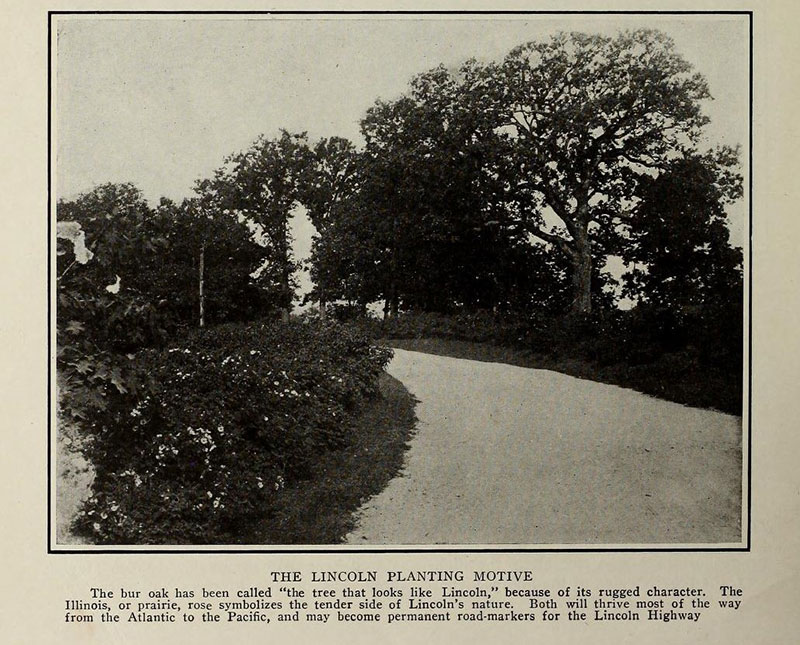

The women wanted the Lincoln Highway to look like a “veritable wild garden.” This was accomplished by utilizing native plant species within each state’s section of the Lincoln Highway. The Illinois or Prairie Rose was to be most utilized, followed by the Burr Oak tree, and laurels.

Both the rose and the oak were selected as road markers for the Lincoln Highway, as they would thrive along most of its length, and for their intrinsic connection to Lincoln. The Burr Oak was commonly referred to as “the tree that looks like Lincoln,” because of its rugged character, while the Prairie rose symbolized the tender side of Lincoln’s nature.

“If that vast thoroughfare which is to run from the Atlantic to the Pacific…is the result of masculine imagination, the decoration of it, the women have determined, shall be their care.”

- Farmer City Journal, May 15, 1914.

Photograph: View of a completed planting of Burr oaks and Prairie rose in Illinois published in The American City (Town and Country Edition), April 1916.

Mrs. E. E. Kendall

The general chairman of the Lincoln Highway Beautification Committee was Chicagoan, Mrs. E. E. Kendall. Under Kendall’s leadership, a national tree-planting movement was catalyzed along the length of the Lincoln Highway.

Using her influence within the General Federation of Women’s Clubs, she urged each state chapter to dedicate itself to the planting of trees along the highway. Kendall planned native trees for each state based on the findings of the Lincoln Highway Beautification Committee. She also proposed that each Women’s Club chapter dedicate “memorial miles,” which would ensure perpetual care of the trees by members.

“The ideal of this committee will be a characteristic, artistic and harmonious, ocean to ocean boulevard, which will surpass anything in the history of the world, which will serve our people and attract tourists not only from our own country but from foreign lands”

– Mrs. E. E. Kendall, Argus-Leader, Sioux Falls, October 12, 1915.

Photograph: The Chicago Tribune, May 26, 1914.

Julia "Billy" Burke & Sophie "Teddy" Karlin

In 1922, Julia “Billy” Burke and Sophie “Teddy” Karlin – and a border collie named “Buster”- finished a journey across the country along the Lincoln Highway. The young women traveled on foot mostly, hopping in train coal cars in the desert. They told stories of being chased by cattle, picking grapes off vineyard vines, and selling newspapers to make money. Teddy and Billy went by traditionally male names and wore men’s clothing, both as a safety measure and a matter of practicality. Buster, who started as a puppy, had grown into a full-grown dog by the end of the journey.

“The most dangerous thing that happened on the way was the fact that Teddy had three proposals. However, none of the three looked sufficiently good to justify interrupting the trip.”

- San Francisco Chronicle, October 3, 1922.

Photograph: San Francisco Chronicle, October 3, 1922.

701 Essington Road, Suite 100 Joliet, IL 60435 (844) 94-HCCVB (844-944-2282)